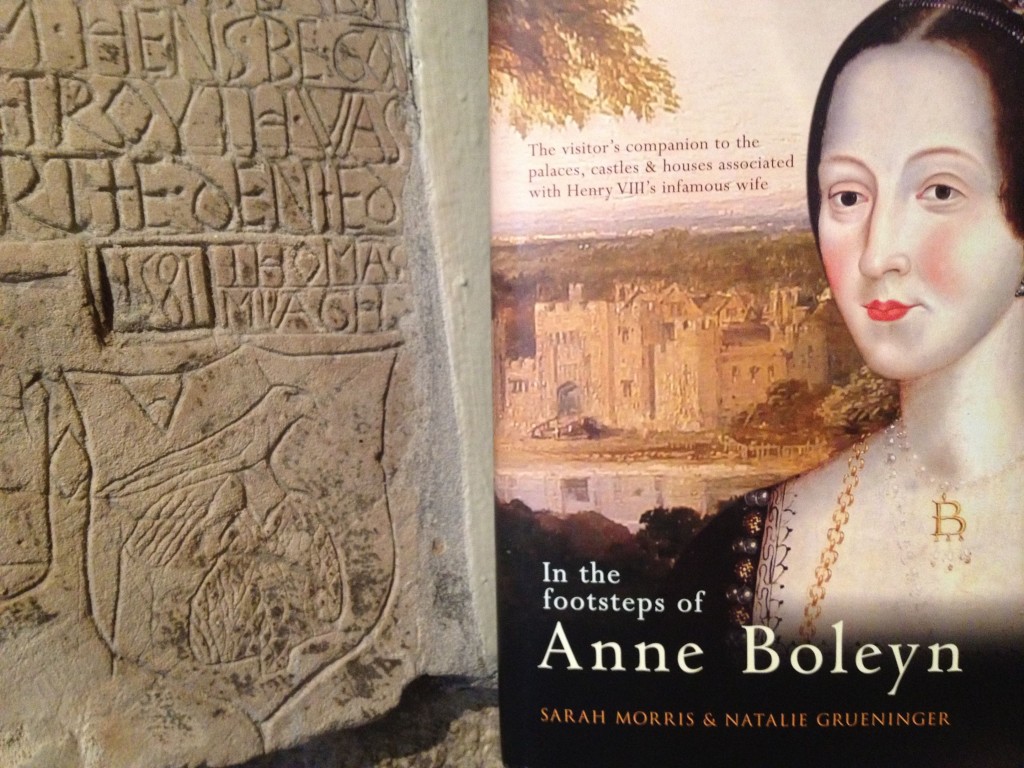

Sarah Morris and I are delighted to share with you an excerpt from our book, In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn. It is a detailed guide to the Tower of London, as known to Anne Boleyn. We do hope you enjoy walking in Anne’s footsteps!

Reproduced here by kind permission of Amberley Publishing.

Natalie

The Tower of London

“It comes to a thousand days – out of the years. Strangely just a thousand. And of that thousand – one – when we were both in love. Only one when our loves met, and overlapped and were both mine and his.”

Maxwell Anderson: Anne Boleyn’s fictional speech from the Tower in Anne of the Thousand Days, 1948

Of all places associated with Anne’s story, there is nowhere more poignant perhaps than the Tower of London, that mighty Norman fortress first constructed by William the Conqueror shortly after the said Duke of Normandy invaded England in 1066. Situated in Central London on the north bank of the River Thames, it has looked over the City of London for over 900 years and has served as a royal palace and fortress, prison and place of execution, an arsenal, a royal mint, a royal menagerie and jewel house.

Within the shadows of its walls, Anne experienced both the pinnacle of her triumph – as she lodged at the Tower with Henry in sumptuous splendour prior to her Coronation in 1533 – and the darkest days of her cataclysmic downfall almost 1,000 days later in May 1536. The only other time that we know that Anne visited the Tower was during the first week of December 1532, shortly after she and Henry had returned from Calais.

During that visit, the king and Anne, then Marquess of Pembroke, inspected the new queen’s lodgings, which were being constructed for Anne in advance of her Coronation the following year. At the same time, the king showed Anne the interior of the Jewel House, which once abutted the southern wall of the White Tower. This was a great honour indeed. Many items of gilt and partially gilt plate were transferred to adorn Anne’s increasingly lavish household during that December; did the royal couple select the items from here? We can only begin to imagine what sights Anne laid eyes on for the first time that day, as the Jewel House was then used to house the Crown Jewels and coronation regalia, later to be used in her own coronation ceremony on 1 June 1533 (see also ‘Westminster Abbey’).

And so no Tudor pilgrimage is complete without a visit to the Tower, but, with its complex and varied history spanning almost 1,000 years, it’s easy to miss some important Anne connections. Let’s explore these highlights together!

St Thomas’s Tower

Much of the medieval palace was restored in 1532 in preparation for Anne’s Coronation the following year. St Thomas’s Tower was at this time largely rebuilt and provided accommodation for two of Henry’s senior household officials, the Lord Great Chamberlain and Lord Chamberlain, who were responsible for orchestrating the magnificent coronation ceremonies. It’s still possible to see the fortified beck and timber walls that Henry had installed for this extravagant event. They certainly needed to be strong to withstand the weight of the ceremonial guns. According to Tudor chronicler Edward Hall, Anne’s arrival was marked by the firing of 1,000 cannon!

The Wall Walk

You exit the Wakefield Tower via a spiral staircase, which leads you to the South Wall Walk. Continue along this stretch of walk towards the Lanthorn Tower and pause about halfway. Look out towards the open grass area in front of the White Tower; this area was once enclosed and contained a Great Hall, where Anne and George Boleyn were tried in 1536, and the queen’s lodgings, specially built for Anne’s Coronation (see below, The Royal Apartments). In a merciless twist of fate, she would spend her final days and darkest hours in the very same apartments that only three years earlier had played host to such revelry and lavish celebrations.

Continue along towards the Salt Tower, used as a prison in the Tudor period, and follow the wall walk until you reach the Martin Tower.

The Martin Tower

As you enter, look out for the carving that reads ‘boullen’. George Boleyn may have carved it, as tradition has it that he was imprisoned here. Although there is no conclusive evidence to prove it, it’s plausible, considering the Martin Tower did house prisoners in Tudor times.

From 1669, it’s where the Crown Jewels were displayed and today houses an exhbition – ‘Crowns and Diamonds: the making of the crown jewels.’ Sadly, none of these jewels have an Anne connection.

From the Martin Tower you descend into the inner ward; from here make your way towards the Beauchamp Tower and another Boleyn carving.

The Beauchamp Tower

This time the carving is of Queen Anne’s falcon badge – minus its crown and sceptre – and can be found etched in a first-floor cell of the thirteenth-century Beauchamp Tower. There it competes for space with a sea of graffiti left by Tudor prisoners. The Beauchamp Tower’s spacious accommodation and proximity to the constable and his deputy made it a perfect place to house prisoners of high rank. In Mary I’s reign John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, and his five sons were all imprisoned here. This tower is also home to another important Tudor graffito; the name ‘Jane’ is roughly carved into the stone of the upper chamber. It is thought that Lady Jane Grey’s distraught husband, Guildford Dudley, inscribed it during his imprisonment in 1553–4. But what of Anne’s carving?

Did one of the men arrested alongside her hastily scratch her uncrowned falcon badge into the wall as a final display of loyalty to a queen they knew to be innocent? It’s possible. And the fact that Anne’s falcon has been stripped of its royal regalia, like its mistress, is most poignant.

Did one of the men arrested alongside her hastily scratch her uncrowned falcon badge into the wall as a final display of loyalty to a queen they knew to be innocent? It’s possible. And the fact that Anne’s falcon has been stripped of its royal regalia, like its mistress, is most poignant.

As you leave the building and cross Tower Green take note of the scaffold site on your left but keep in mind that although it’s a touching memorial, it is not the site of the scaffold upon which so many notable Tudor personalities, including Anne, lost their lives (see below, Anne’s Final Walk to the Scaffold Site). Make your way now to the oldest of all the medieval buildings and perhaps the most imposing, the White Tower.

The White Tower

There is much of interest for the Tudor enthusiast in this ancient structure, begun by William the Conqueror in the 1070s, including a wonderful display from the Royal Armouries’ collection on the ground floor (don’t miss the suits of armour belonging to Henry VIII and his son, Edward).

Much of the interior was refurbished for Anne’s Coronation, as the White Tower played an important role in the coronation rituals. On Friday 30 May 1533, eighteen Knights of the Bath were created and each candidate was required to take part in an overnight vigil in various chambers in the White Tower. On the first floor, the Chapel of St John the Evangelist is a must-see, as it’s said to be one of the best-preserved Norman chapels in the world. It’s not known whether Anne visited the chapel for certain but it remains a distinct possibility. Let’s now turn our attention to these once-grand apartments that saw both triumph and tragedy.

The Royal Apartments

From Thursday 29 May to Saturday 31 May 1533 and from Tuesday 2 May to Friday 19 May 1536, Anne was accommodated in the queen’s lodgings, part of the royal apartments, which were situated in the south-east corner of the Tower. She was not, as a Victorian myth later propagated, accommodated during her imprisonment in the Queen’s House, which was built several years after Anne’s execution and can still be seen overlooking Tower Green today.

There had been royal apartments on that site, in one form or another, since 1220. During the reign of Henry II, a permanent inner ward was created and separate lodgings for both the king and queen were constructed, including a Great Hall (later to bear witness to the trials of Anne and George Boleyn). At the turn of the sixteenth century, Henry VII significantly enlarged the king’s lodgings, with the addition of a tower (containing the king’s library and closet) in 1501, with a gallery bisecting the new privy gardens following in 1506.

Then, in 1532, Henry VIII ordered Cromwell to organise the construction of a whole new suite of rooms, in order to honour Anne as his queen-to-be. The additional space was also necessary to house the entire court during the two days of festivities and to provide a majestic backdrop to the opulent ceremonies that took place in the Tower prior to Anne’s ceremonial entrance to the City on Saturday 31 May.

An engraving of the Tower made in 1597 shows the lodgings as Anne would have known them. Unfortunately, today they are all but lost, except a few foundation stones that give us an inkling of their former existence. However, if you find the south lawn, directly south of the White Tower, you will be looking over what was once the tower’s inner ward, as described below. Here, once again, you will need your imagination!

The entrance to the inner ward was through the mighty Cold Harbour Gate. Remnants of the gate can still be seen abutting the west wall of the White Tower today. Once inside the inner ward, in front of you would have been a complex of buildings arranged around an irregular triangular ‘courtyard’. Running diagonally from the Cold Harbour Gate toward the Great Hall was a line of brick-built Tudor lodgings/offices; the thirteenth century Great Hall occupied the southernmost aspect of the courtyard (roughly where the modern-day café and bookshop are situated), while a series of buildings ran at right angles from the hall toward the south-east corner of the White Tower and the Wardrobe Tower, thereby completing the far side of the courtyard. These latter buildings formed the newly built queen’s apartments. Finally, abutting along the southern wall of the White Tower was the Jewel House, referred to above.

Anne’s new suite of rooms was palatial, consisting of six chambers, including a 70-foot by 30-foot great watching chamber, a presence chamber, privy chamber, closet/oratory, bedchamber and another large chamber (possibly a dining chamber). All rooms were decorated in the most fashionable Renaissance style. A flight of stairs led down directly from Anne’s privy rooms into the courtyard. It seems that it was down those stairs that Anne was led to first her trial and then, three days later, to her execution. Read more about Anne’s final walk to the scaffold in the Myths section below and let’s now proceed to where Anne’s physical remains were buried.

Fast Tube by Casper

The Chapel Royal of St Peter ad Vincula

On the morning of 19 May 1536, Anne Boleyn went bravely to her death in a private execution at the Tower of London. It took only one stroke of the executioner’s sword to sever her delicate neck, the very same neck that the poet Thomas Wyatt had once praised as ‘fair’ in one of his admiring verses. It was then left up to her ladies to move and prepare her body for burial. Anne’s head was covered in a white cloth and carried by one of her attendants. Her body was undressed and ‘wrapped in a white covering’ and placed in an old elm chest that had been used to store bow-staves. Although only a short while ago Anne had been queen, loved and desired by a king, no provision had been made for a proper coffin.

Anne’s women carried her body approximately 65 metres to the royal chapel of St Peter ad Vincula, passing the newly filled graves of Norris, Weston, Brereton and Smeaton, who had been buried in the churchyard adjacent to the chapel only two days earlier. There, Anne’s ladies buried their mistress in the earth beneath the chancel pavement in an unmarked grave (see Myth Five below). Only three years and thirty-seven days after she’d first dined lavishly as Queen of England, she now lay dead and all but forgotten by those at the English court who now chose to turn their back on the past.

It’s possible to visit Anne’s final resting place and pay your respects. The chapel can be accessed through a yeoman warder tour (check the daily programme on arrival) or in the last hour of standard opening time, usually from 4.30 p.m. Other notable Tudor personalities are also buried within the chapel, including George Boleyn, Jane Grey, Catherine Howard, Lady Rochford, Thomas More, John Fisher and Edward Seymour.

Before exiting the Tower complex, head to the Bell Tower, unfortunately not opened to the public, but important as it’s here that the poet Thomas Wyatt spent his imprisonment in May 1536.

Before exiting the Tower complex, head to the Bell Tower, unfortunately not opened to the public, but important as it’s here that the poet Thomas Wyatt spent his imprisonment in May 1536.

The Bell Tower

The Bell Tower was another place regularly used to house important prisoners. Notable personalities like Sir Thomas More and Princess Elizabeth were at one time imprisoned here, and tradition has it that the poet Sir Thomas Wyatt witnessed the gruesome execution of the men accused alongside Anne from his prison in the Bell Tower (or somewhere nearby). He was so deeply affected by what he saw from his cell that he responded by writing a poem about the fate of those who rise and fall at court, Innocentia Veritas Viat Fides Circumdederunt me intimici me, where he emphasised that:

The Bell Tower showed me such sight

That in my head sticks day and night.

What exactly was the ‘sight’ that so affected Wyatt? To follow this trail we need to exit the Tower and visit the site of the scaffold on Tower Hill.

The Scaffold on Tower Hill

On the morning of Wednesday 17 May 1536, George Boleyn, Henry Norris, Francis Weston, William Brereton and Mark Smeaton were led out of the Tower under close guard and beheaded on a high scaffold on Tower Hill. Large crowds, including many courtiers, had gathered to see the bloody end of these once-great men. It was reported that all five men died in a dignified manner and observed scaffold etiquette by confessing their faults and confirming the justness of their punishments in their farewell speeches. What they did not allude to though were the specific crimes that brought them to this terrible fate. The highest-ranking, George Boleyn, faced the axe first but only after he had delivered a very long speech, of which several versions survive, but which commenced:

Christian men, I am born under the law, and judged under the law, and die under the law,

and the law hath condemned me. Masters all, I am not come hither for to preach, but for

to die, for I have deserved to die if I had 20 lives, more shamefully than can be devised, for

I am a wretched sinner, and I have sinned shamefully.

I have known no man so evil, and to rehearse my sins openly it were no pleasure to you

to hear them, nor yet for me to rehearse them, for God knoweth all. Therefore, masters all,

I pray you take heed by me, and especially my lords and gentlemen of the court, the which

I have been among, take heed by me and beware of such a fall.

Norris, Weston, Brereton and Smeaton soon followed. Smeaton, a lowly ranked musician, was the last to die. The sight that lay before him must have been horrendous: the block floating in a sea of red surrounded by butchered bodies and heads. Yet still he managed to find the courage to utter a few words before laying his head on the blood-soaked wood.

The mutilated corpses remained there until Tower officials stripped them of their clothes and piled them onto a cart that transported them to their final resting places: the Chapel Royal of St Peter Ad Vincula for Lord Rochford and the adjacent churchyard for Norris, Weston, Brereton and Smeaton. In the sixteenth century the churchyard extended out to the area now occupied by the Waterloo Barracks.

Today a small square marks the spot of the scaffold on Tower Hill where more than 125 prisoners, including five of Anne’s loyal subjects, lost their lives. The court attempted to turn its back on these bloody events; however two poems, attributed to Thomas Wyatt (although not all historians agree with this attribution), In Mourning wise since daily I increase and Innocentia Veritas Viat Fides Circumdederunt me intimici me, ensured that they would not be forgotten.

In the latter, Wyatt reflects on the fate of those who rose high at court and experienced a reversal of fortune. He ends each verse with a Latin phrase that roughly translates as ‘Thunder rolls around the throne’. Verse three speaks for itself:

These bloody days have broken my heart.

My lust, my youth did them depart,

And blind desire of estate.

Who hastes to climb seeks to revert.

Of truth, circa Regna tonat.

Common Myths about Anne Boleyn and the Tower

Myth One: Anne Boleyn and Traitor’s Gate

On 2 May 1536, Queen Anne was arrested and transported from Greenwich to the Tower of London in full daylight. It is often said that Anne entered the Tower via Traitor’s Gate, the gate below St Thomas’s Tower, but this is incorrect. In Charles Wriothesley’s A Chronicle of England during the Reigns of the Tudors, from A.D. 1485 to 1559 Vol. 1, he states that

Anne Bolleine was brought to the Towre of London by my

Lord Chauncelor, the Duke of Norfolke, Mr. Secretarie, and

Sir William Kingston, Constable of the Tower; and when she

came to the court gate, entring in, she fell downe on her knees

before the said lordes, beseeching God to helpe her as she was

not giltie of her a accusement, and also desired the said lordes

to beseech the Kinges grace to be good unto her, and so they left her

their prisoner.

Court Gate was also referred to as Towergate and if we look closely at the plan of the Tower of London labelled A True and Exact Draught of the TOWER LIBERTIES, survey’d in the Year 1597 by GULIELMUS HAIWARD and J. GASCOYNE, and compare it to a plan of the Tower of London today, it is clear that the building that is labeled ‘The Tower at the Gate’ is today known as the Byward Tower. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when arriving at the Tower, royalty often used this private entrance, which gave access to the Tower from the wharf. Although originally constructed by Edward I, the gate through which Anne passed dates from the fifteenth century and this and the drawbridge can still be seen today. After disembarking the boat and climbing the stairs (today called the Queen’s Stairs) on to the wharf, Anne would have crossed the drawbridge – necessary as the moat was filled until 1843 – and entered the Byward postern gate, exiting onto Water Lane. From here it is unclear exactly what route she took but it would have only been a short walk to the entrance of the royal lodgings where she would spend her imprisonment.

Anne was not the only high-ranking prisoner said to have entered via this gate. Her daughter, Princess Elizabeth, followed in her mother’s footsteps when she arrived at the Tower as a prisoner on 18 March 1554. Her mind must have been plagued with thoughts of her mother’s dreadful end only eighteen years earlier.

(Read more in my article: Anne Boleyn’s Arrival at the Tower of London)

Myth Two: Where Was Anne Imprisoned in the Tower?

Contrary to recent popular films and television series about Anne and the Tudors, Anne Boleyn was not kept in a cell during her imprisonment. Quite befitting her status as queen, she was housed in the same considerable splendour she had known in 1533, occupying the same queen’s lodgings as have been described above for the entire duration of her stay at the Tower.

Myth Three: Anne’s Final Walk to the Scaffold Site

When Anne emerged from her lodgings early on the morning of 19 May 1536, resplendent in a grey damask gown lined with fur and an English gable hood, she was probably led down a flight of steps that appears to have stood in the north-east corner of the inner ward leading directly down from Anne’s privy rooms. Headed by Sir William Kingston – and with a guard of 200 of the king’s bodyguard in attendance – Anne made her way along a path in front of the Jewel House (this no longer exists, but once abutted the south wall of the White Tower) toward the Cold Harbour Gate. Swinging right and passing under the shadow of the gate, Anne continued her walk northwards to the scaffold site.

Again Victorian myth leads many visitors to believe that the original scaffold site is on the current site of Tower Green in front of the Beauchamp Tower. This is erroneous and not helped by a poignant monument to the executed, which was unveiled there in 2006.

However, to stand on the site of the original scaffold you need to head across the parade ground (on the north side of the White Tower) toward the entrance to the Waterloo Barracks and the exhibition of the Crown Jewels. There, roughly in front of the entrance, was the site of the place where Anne died at the hands of the Sword of Calais, the French executioner from St Omer.

Myth Four: Anne Saw George’s Execution

As we have already established, Anne Boleyn was detained throughout her imprisonment at the Tower in the queen’s lodgings, situated in the south-east corner of the Tower precinct. Given the topography of the place and the position of the scaffold on Tower Hill to the north-west of the fortress, it becomes clear that it would have been impossible for Anne to witness the execution of her brother and the other four men who suffered with George Boleyn on the scaffold that day. The only way this might have been possible would have been if Anne had been escorted to one of the towers on the north or west side of them Tower, specifically to watch the men die their bloody deaths. The only hint we have that the condemned queen might have been forced to watch the men die comes from Chapuys in one of his dispatches, although Ives in his biography of Anne dismisses this on account of the logistics involved in moving such a high-profile prisoner.

Myth Five: Is Anne Buried Beneath Her Memorial Plaque?

There exists some debate as to exactly where in the chancel Anne’s body was buried. In October 1876, the chancel was restored with Queen Victoria’s approval as part of a larger restoration project that hoped to address the dilapidated state of the chapel and bring it back to its original condition. It was known that Queen Anne Boleyn, George Boleyn, Lady Rochford, Catherine Howard, the dukes of Somerset, Northumberland and Monmouth and the Countess of Salisbury were buried there, and so work proceeded with great care under the supervision of a team of six people including the Resident Governor of the Tower. The findings were documented by Doyne C. Bell in Notices of the Historic Persons Buried in the Chapel of St. Peter Ad Vincula in the Tower of London (1877).

The team claimed to have consulted various historical sources and from these documents produced a plan showing where they believed the persons had been originally buried. On 9 November 1876, the pavement above the spot marked on the plan as the final resting place of Queen Anne was lifted and the earth removed to a depth of 2 feet. Here the bones of a female were found and, after a thorough examination, all present were convinced that the remains they had uncovered were those of Anne Boleyn who, according to Bell, was recorded as being buried in front of the altar by the side of her brother George.

George Boleyn’s remains were not discovered during the restoration and so were either removed or buried further towards the north wall, an area that remained undisturbed. The description offered by Dr Mouat (Local Government Inspector), who examined the bones, is very much in keeping with what we know of Anne’s appearance with the exception of one comment – ‘a rather square full chin’. The bones were also identified as belonging to a female of between twenty-five and thirty years of age, perhaps another discrepancy; however, the debate about Anne’s year of birth is not one to explore here!

In addition, the committee also recorded that they had uncovered the remains of Lady Rochford and Margaret, Countess of Salisbury, near the south wall. Bell recorded that the bones believed to belong to Lady Rochford were of a female of ‘rather delicate proportions’ of between about thirty and forty years of age.

Catherine Howard’s remains were not found and the explanation offered was that, because she was so young at the time of death, her bones were not yet hard and so the lime used in the interments turned her bones to dust.

Historian Alison Weir offers an alternative explanation. She believes that the bones identified as belonging to Anne Boleyn might in fact be those of Catherine Howard, who was aged between sixteen and twenty-three years when she was executed and whose miniature by Holbein may show her with what could be described as a square chin. Weir also argues that the remains identified as Lady Rochford by the Victorian committee are in fact those of Anne Boleyn. It’s an interesting theory; however, as this has only been intended as a brief overview of the case, you can examine it in more detail by reading Doyne C. Bell’s findings and Alison Weir’s arguments in The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn.

Anne’s death did not bring about an end to the controversy that surrounded her in life and, after almost half a millennium, continues to trail her in death. What is certain is that in the end, on 13 April 1877, the remains of those exhumed from the chancel were reinterred where they had been found and there they remain until this day, marked only by a Victorian memorial plaque. Each year on 19 May, the muted hues of the marble pavement in front of the altar accentuate the beauty of the red roses sent by anonymous admirers to commemorate the life of this remarkable woman.

(Read more about Anne Boleyn’s remains and the restoration of the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula here.)

Authors’ Favourites

Before visiting, we strongly urge you to watch a brilliant video on YouTube by Historic Royal Palaces; it will help you visualise Anne’s apartments at the Tower. It charts the process of the digital recreation of Anne’s Boleyn’s lodgings (Search on YouTube for ‘Anne Boleyn’s apartments – HM Tower of London’) Sadly, you cannot actually walk in Anne’s footsteps from the site of her lodgings to the scaffold. However, do find the real site of the scaffold and go and stand there. Take a look around and you will see, almost unchanged, the last sight that met Anne’s eyes before she was executed.

Finally, if you ever get chance, travel to the City of Winchester and see an extant Great Hall, built at the same time as the one at the Tower by the same king – Henry III. It probably looks very similar to how the Great Hall at the Tower once looked. Standing under its cavernous, vaulted roof, gives you a very good idea of the size, grandeur and acoustics of the hall and how Anne might well have felt at her trial in 1536.

Visitor Information

The Tower of London is managed by Historic Royal Palaces. For more information on how to reach the Tower and its opening hours, visit the Historic Royal Palaces’ website at http://www.hrp.org.uk/TowerOfLondon, or telephone + 44 (0) 2031 666000. Postcode for the Lower Thames Street Car Park (Tower of London): EC3R 6DT.

You can purchase ‘In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn’ from The Book Depository, which offers free shipping worldwide. The book is also available from Amazon, direct from the publisher and at bookstores throughout the UK.

First published 2013 Amberley Publishing The Hill, Stroud Gloucestershire, GL5 4EP www.amberley-books.com<http://www.amberley-books.com> Copyright (c) Natalie Grueninger & Sarah Morris, 2013 The right of Natalie Grueninger & Sarah Morris to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 1 4456 0782 5

Lovely read that Natalie.

It’s a fascinating place the Tower isn’t it. Every time I’ve been I noticed something ‘new’ I didn’t see before. And it’s presentation to the public has become a lot more visual, informative and hands on since the first time I visited it in the 1970’s. It makes it such a more interesting place to spend the day, especially for younger ones, who need the extra visuals to keep their interest up.

If only those walls could talk to us eh!! I would love to get locked in there over night, to feel it’s atmosphere when it was still and empty…not on my own thought, I’m not that brave 🙂

Those lines spoke in the film by Anne are very poignant, you can imagine her saying them in real life…