Was Anne Boleyn’s downfall in 1536 a result of Henry’s jousting jealously?

By Emma Levitt

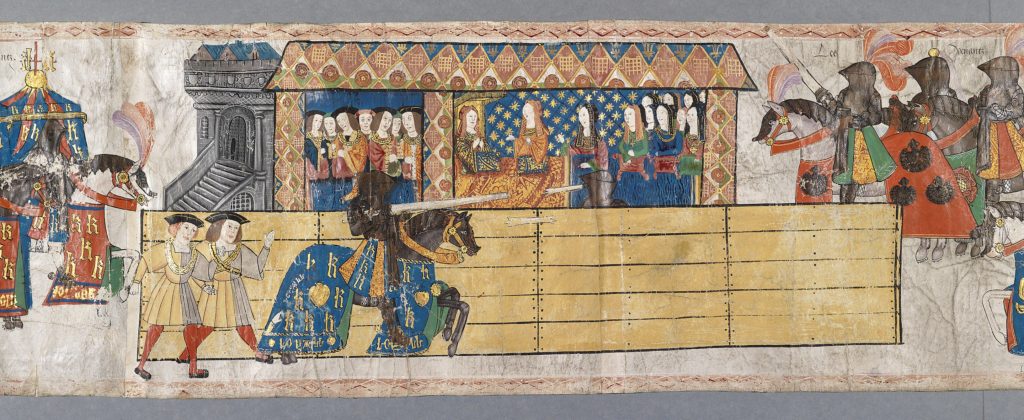

On 1 May 1536, King Henry VIII and Queen Anne Boleyn attended the annual May Day tournament at Greenwich Palace. According to Lancelot de Carles – who wrote a narrative poem of Anne’s rise and fall a month later – Henry Norris, George Boleyn, William Brereton, and Francis Weston competed in the tournament. The queen’s brother, Lord Rochford led the team of Challengers and Norris, the king’s Groom of the Stool, led the team of Answerers. Henry was left sitting out for one of the first times in his reign, due to a riding accident he had suffered in January of that same year, which had left him with a serious leg injury and unable to joust. All was going well until; as chronicler Edward Hall records: ‘sodainly from the lustes the kyng departed hauyng not aboue vi. persons with him, and came, in the euenyng for Grenewyche in his place at Westminster’. The next day Norris, along with other jousters Rochford, Brereton and Weston were all taken to the Tower of London and soon afterwards were executed for having been partners in Anne’s alleged adultery. In previous analyses of Anne Boleyn’s downfall historians have commonly emphasised adultery, faction and fertility, but no one has given detailed consideration before to the episode in terms of Henry’s relationship with the men and their prominence in the tiltyard. In reviewing this episode in the context of Henry’s masculine status it offers an alternative explanation for why these men fell so quickly. The men with whom Anne was accused were not chosen at random, or even because they were known to be friends with her. They tend not to be considered in great detail because everyone focuses on Henry and Anne, thus the men are almost peripheral. Yet the identity of the men and their status as jousters was absolutely crucial, as it was these men that posed a threat to Henry’s masculinity because of their jousting abilities, rather than their relationship with Anne.

Anne Boleyn, attributed to John Hoskins

Henry loved to joust. He had been forbidden from competing during his father’s reign as Henry VII had wanted to protect his only surviving male heir. As soon as he was able Henry began training for jousting contests. In September 1509 the Venetian Ambassador Andrea Badoer wrote home that the king had been ‘tilting at the ring’ at the palace of Westminster. Running at the ring sought to develop accuracy in hitting a target. Participants took turns to ride along the barrier in the tiltyard before taking aim with their lance at a ring suspended from a post that replaced the opponent in a genuine contest. In a practice not dissimilar to scoring jousting, whoever speared the ring with his lance the most times after a set number of courses would be declared the winner. Henry knew that he had to put in some serious practice if he was to stand a chance of jousting against the sporting elite of the Tudor court who had years of training behind them. The decision to then compete as king sent a clear message that Henry was fashioning his kingship on a traditional medieval model of manhood. It was in the tiltyard that men were able to prove their masculinity by performing feats of arms in front of other men and women. In order to prove that he was genuinely endowed with the properties and accomplishments of knightly masculinity, it was vital to Henry that he should engage in real competition with skilled jousters. The hours that Henry spent training in the tiltyard were not wasted they were at the very heart of his identity as a king and as a man.

Detail from the 1511 Westminster Tournament Roll, showing Henry VIII jousting in front of Katherine of Aragon.

This is exactly what Henry was doing in January 1536 when he suffered a riding accident whilst training for the upcoming May Day tournament. Many modern commentators still mistake Henry’s fall, as happening during a joust, yet there is no recorded evidence of a tournament taking place at Greenwich in January 1536. There are three main contemporary reports of the king’s accident: one from the Spanish ambassador Eustace Chapuys, another from chronicler and herald Charles Wriothesley and one from Dr Pedro Ortiz, Charles V’s ambassador in Rome. Arguably Wriothesley’s chronicle is the most revealing on this point, he writes: ‘for the King ranne that tyme at the ring and had a fall from his horse, but he had no hurt’. According to Wriothesley, the king was training in his tiltyard at Greenwich, as he had been known to do from the start of his reign by ‘running at the ring’. It is apparent from Wriothesley’s description that Henry was practicing his jousting skills, not in fact competing in a live joust.

As it was, it seems that the king had taken a huge blow to the head and badly injured his legs. The Spanish ambassador Chapuys reported on 29 January 1536 that: ‘the king being mounted on a great horse to run at the lists, both fell so heavily that every one thought it a miracle he was not killed’. Dr Ortiz on the 6 March 1536 claimed that he had a received a letter from the ambassador in France, who had heard from England, that: ‘the king of England had fallen from his horse and been for two hours without speaking’. We do not know for certain if Henry was unconsciousness for two hours, but what is clear is that the king was knocked off is horse, which in turn fell upon him, and marked the start of his debilitating health problems.

Henry VIII by Joos van Cleve, c. 1535.

For Henry most devastating of all was the end to his jousting career. The king now unable to actively participate in tournaments must have resented this display of continued vigour from his former jousting companions. Of all the men, Henry Norris was Henry’s oldest and closest friend. Norris knew Henry intimately as his Groom of the Stool; he attended on the king as he used the lavatory. Being in such close physically proximity to the king, it is no wonder that Henry formed such a strong bond with Norris. Norris was known at the Tudor court to have been, ‘best loved of the King’. Norris was also a formidable opponent in the joust. Norris was fifty-four when he competed in the May Day Tournament, nearly ten years older than the king who was forty-five. But despite being so much older, Norris, unlike Henry, could still joust, whilst the king had been forced to retire. Indeed, Henry had doubtless assumed that he would still be jousting in his fifties like Norris, not having to stop in his forties. Norris’ horse shied at the lists, and so Henry generously offered his own, knowing that Norris ‘could not keep it long’. Henry now viewed Norris not as a friend, but as a rival, made all the more obvious by his own inability to joust.

Portrait believed to be of Francis Weston, by unknown artist.

Other men who competed in the tournament included Francis Weston and William Brereton who were both involved in the charges against Anne along with Rochford. In fact of the men accused alongside of Anne, only Mark Smeaton did not compete in the May Day tournament, yet as a court musician his status was not fitting to the exclusive arena of the tiltyard. All the other men accused with Anne were Henry’s jousting companions including Thomas Wyatt who competed at Greenwich and was arrested, but later released. Perhaps to a certain extent Henry did genuinely believe that Anne would have cuckolded him with these handsome and athletic knights who were still able to showcase their chivalrous masculinity by competing in jousts when he could no longer impress in the tiltyard.

Weston was only twenty-five when he competed in the May Day tournament, thus twenty years younger than the king. In his prime of manhood by contemporary standards, Weston must have served as a reminder to Henry that he was well past this youthful phase of masculinity. Weston became caught up in the game of courtly love with the queen, along with Norris, which was a dangerous dalliance, especially given his youthfulness.

Brereton was forty-nine when he competed in the May Day tournament, being only a few years older than the king. Ives has identified that Brereton did not belong to Anne’s close circle and he argues his ‘innocence in respect of Anne is beyond question’. In relation to Brereton’s downfall, it is likely that Henry allowed him to be added to Thomas Cromwell’s list of suspects, as like Norris his ability to keep jousting and continuing displays of manhood humiliated the king.

Rochford thirty- three years old condemned himself to death. He was handed a piece of paper that addressed the question of Henry’s sexual ability. Although he was told not to read it out aloud to the court, he did so, and this was said to have sealed his fate. Anne had reportedly said to Rochford that: ‘he [Henry] has neither vigour nor virtue’. This was a serious blow to Henry’s manly pride and something about which he was increasingly anxious. Henry had still failed to produce a male heir in his marriage to Anne and to make matters worse he had been forced to retire from the sport that had confirmed his masculinity from the start of his reign.

Previously all discussions have focused on these men’s interactions with Anne, but alternatively I have placed emphasis on their relationship with the king something which has been entirely overlooked in the past. Henry was no doubt encouraged to remove these jousting men from his chamber and to put an end to tournaments at his court, so that any threat to his masculine image was swiftly removed. Henry’s jousting jealously over men such as Norris, Weston, Brereton and Rochford was such that he acted in haste to eliminate all competition in order to ensure that his kingship and manhood remained unchallenged both in and outside of the tiltyard.

Latest Comments