I’m thrilled to be hosting Day 4 of Melita Thomas’ blog tour for her latest book, The House of Grey: Friends and Foes of Kings. To mark this special occasion, Melita has written a wonderful guest post about the Grey family’s perspective on Anne Boleyn.

Over to Melita!

Divided loyalties?

For a king to be unfaithful to his wife was not especially unusual. The English court was therefore unlikely to have been surprised in 1525 when King Henry VIII began to pay marked attentions to Mistress Anne Boleyn, daughter of one of his ambassadors, Sir Thomas. Henry had had liaisons before – six years earlier, Bessie Blount had borne him a son, and, although few people at the time knew, he had had some sort of relationship with Anne’s sister, Mary.

What did astonish Henry’s courtiers was the gossip that began to circulate in 1527, that the king was questioning the legality of eighteen-year-long marriage to Katharine of Aragon. Even more outlandish was the revelation that Anne was not physically his mistress, and that he planned to marry her, once the annulment he confidently expected to be granted by Pope Clement VII, had arrived from Rome.

Pope Clement VII, Public Domain.

Had matters gone as Henry hoped – a quick annulment, the retirement of Katharine to a convent, and the retention of their daughter, Princess Mary, in the succession after any sons by Anne, his courtiers would probably have done no more than bend their knees to the new queen, whilst raising their eyebrows behind their hands. But Henry had not taken into account Katharine’s steely determination and her implacable resistance to the annulment. Before long, the tussle between the king and queen was making the lives of Henry’s friends, family, councillors and courtiers extremely difficult.

Like many other noble families of the day, the Greys were divided on the issue. The head of the family, Thomas Grey, 2nd Marquis of Dorset, had been a devoted friend and servant of the king, who was also his cousin, but his younger brother, Lord Edward Grey served in the household of Mary, the French Queen, who disliked Anne, and sided with her sister-in-law. His sister, Lady Margaret Grey, was a maid-of-honour to the queen, whom his mother and his wife had known and respected since she first came from Spain.

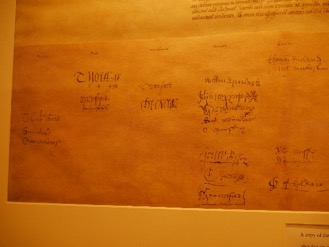

In 1529, when Dorset had to prove his loyalty, he had no hesitation, so far as we are aware, in siding with his cousin. He gave evidence favourable to the king’s cause in the court case convened to examine the marriage, by confirming that he had attended the baptism of both the king and his deceased elder brother, Prince Arthur, that he had been present at the marriage of Arthur and Katharine in 1501, and that he had no doubt that that union had been consummated. He was also one of the nobles who signed a letter to the pope, requesting the annulment be granted.

A facsimile of the letter to Clement VII, requesting the annulment. 2nd Marquis of Dorset’s signature is in 4th column, 2nd from bottom © Melita Thomas

That Dorset was a genuine supporter of the annulment may be inferred from his will of 1530, made whilst Henry and Katharine were still married, and Anne although constantly at the king’s side, officially no more than the queen’s maid-of-honour. He left ‘my lady Anne Boleyn’ the sum of £20. Meanwhile, perhaps hedging his bets on the future, he had placed his oldest son, Lord Henry Grey, in the household of the king’s illegitimate son, now Duke of Richmond, and his eldest daughter, Lady Katherine Grey, in that of the Princess Mary, still spoken of as Princess of Wales.

Dorset died in 1530, leaving his widow, Margaret, and his siblings, to navigate the tricky waters of a court that was increasingly polarised. His brother, Lord Leonard, was commanded to accompany the king and Anne to Calais in 1532. Leonard tried to wriggle out of it, almost certainly for the genuine reason that he was short of money, rather than any objection to Anne. Nevertheless, the king was adamant, and Leonard borrowed money from his friend, Thomas Cromwell, to make the trip.

After Hans Holbein the Younger, Margaret Wotton, Marchioness of Dorset. (Public Domain)

Leonard’s sister, Lady Dorothy Grey, was in a particularly difficult position. Her husband, Lord Mountjoy, had been Chamberlain to Katharine since Henry’s accession. He had the unenviable task of telling Katharine, in May 1533, that her marriage had been annulled and that she was demoted to the rank of princess-dowager of Wales. Katharine’s utter refusal to accept these bitter pills and her anger with Mountjoy, led him and Dorothy to withdraw physically from Katharine’s presence, whilst Mountjoy sent letters to the king’s new advisor, Thomas Cromwell, pleading to be allowed to relinquish his office.

Margaret was a prominent participant in the coronation of Queen Anne, riding in a chariot alongside the new queen’s step-grandmother, the dowager-duchess of Norfolk. Her son was honoured by investiture as a Knight of the Bath, before the ceremony. At the same time, her daughter, Katherine, remained in Princess Mary’s household and Margaret dined with the princess on at least two occasions before Mary was degraded and branded illegitimate after the birth of Anne’s first daughter in 1533.

Lord Leonard continued in favour – he had an audience with both the king and Anne before departing for his new post as Chief Marshal of the Army to Ireland in 1535, at which Anne gave him a chain of gold, taken from her own waist, and a purse of sovereigns. Almost simultaneously, his sister, Elizabeth, Countess of Kildare, who retained her loyalty to Katharine of Aragon, was keeping the Imperial ambassador, Eustace Chapuys apprised of events at court, especially when they were to Anne’s detriment. Neither Elizabeth nor Dorothy, however, went so far as to deny Henry’s Acts of Supremacy or Succession and nor did the siblings’ differing reactions to the enthronement of Anne seem to have any effect on their relationship with each other.

In the next generation of Greys, their Protestant zeal led them first, to attempt to oust Katharine’s daughter from the throne, in favour of one of their own, Lady Jane Grey, and, later, to be loyal supporters of Anne’s daughter, Elizabeth I.

For more on the Greys and their relationships with the family of Anne’s successor, the Seymours, see tomorrow’s blog at janetwertman.com.

About the Author

About the Author

Melita’s first book, The King’s Pearl: Henry VIII and his daughter Mary was published by Amberley in 2017.

Melita is also the co-founder and editor of Tudor Times, a repository of information about Tudors and Stewarts in the period 1485-1625.

Connect with Melita

Tudor Times: Tudor Times

Facebook: Tudor Times

Twitter: @thetudortimes

Latest Comments