So much about Anne Boleyn’s early years and time spent in France is unknown and open to speculation.

Most historians though do agree that Anne Boleyn stayed in France, in the household of Queen Claude, for almost seven years, a period for which, according to Eric Ives, ‘we have no direct evidence’ (Pg. 29).

What we do have is local French tradition linking Anne Boleyn with Brie-sous-Forges, a town located southwest of Paris.

According to folklore Anne Boleyn lived at Brie-sous-Forges sometime in her youth, in the castle owned by Du Moulin, friends of the Boleyns. All that remains of the medieval castle today is the Tour of Anne Boleyn and as Alison Weir points out, there is also a street named after her (Pg. 85).

But what evidence is there to support this tradition?

Nicholas Sander, who was no friend of the Boleyns, in 1587, stated that:

‘At fifteen she [Anne] sinned first with her father’s butler, and then with his chaplain, and forthwith was sent to France, and placed, at the expense of the king, under the care of a certain nobleman not far from Brie.’ (Sander, pg. 25)

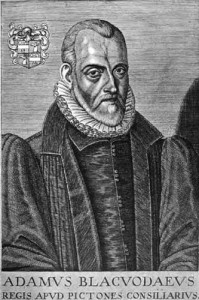

In his notes, Sander adds that in Adam Blackwood’s Martyre de la Reine d’Ecosse, it is said that the nobleman was a friend of Sir Thomas Boleyn.

It seems that Sander was embellishing a story that another sixteenth century writer, William Rastell, had already told.

It is important to note that Rastell was Sir Thomas More’s editor and biographer and therefore hostile towards the Boleyns. He claimed that at the age of fifteen, ‘Anne Boleyn was caught in a compromising situation with one of her father’s servants and was sent to France in disgrace’ (Weir, Pg. 82).

Apart from the fact that Sander is a hostile source who also claimed that Anne had a projecting tooth, six fingers and a wen under her chin… the date given makes this account highly unlikely for if we accept that Anne Boleyn was born c. 1501 then she was fifteen in 1516, a time when more reliable sources tell us she was in the service of Queen Claude.

Even if we accept that Anne was born in 1507, the story still does not fit in with what we know of Anne’s life, as she would have been fifteen in 1522 and back at the English court.

Weir does thought point out the possibility that Rastell may have confused Anne with her sister Mary and that Sander may simply have followed suit.

So the story, although obviously embellished by Sander, might have been referring to Mary Boleyn and not Anne.

However, there are other sources that corroborate the French connection.

Julien Brodeau, in his work about the life of Charles Dumoulin published in 1654, states that ‘Anne Boleyn was brought up in Brie-sous-Forges by a relation of du Moulin’ (Weir, Pg. 85).

The relation, according to Weir, is Philippe Du Moulin (d.1548), ‘Seigneur of Brie and cup-bearer to Francois I’ (Pg. 85). Interestingly, Philippe Du Moulin married Marie de Boulan, said to have been a relation of the Boleyns.

The Almanac of Seine-et-Oise (1790) states, ‘At Brie-sous-Forges, we see in this place the remains of the old castle where they claim was brought up the famous and unfortunate Anne Boleyn, the second wife of Henry VIII of England and mother of Elizabeth I.’ (Weir, Pg. 85)

In contrast to what Weir states in her book about Mary Boleyn, Warnicke claims that Sander’s remarks are the origin of this ‘legend’ (Pg. 246) and that Brodeau quoted both Sander and Blackwood as his sources, incorrectly identifying Philippe Du Moulin as a relation of the Boleyns (Pg. 246).

Warnicke concludes that ‘the whole legend is undoubtedly a fabrication based on Sander’s incorrect claim that her sexual misconduct as a child caused Sir Thomas Boleyn to send her to France to be educated’ (Pg. 247).

Warncike though does not take into consideration Rastell’s claims and the possibility that it was in fact Mary, not Anne, which ‘was caught in a compromising situation’.

I believe that there still exists the possibility of a Boleyn connection to Brie-sous-Forges but I don’t for a moment believe Sander’s tale of Anne’s sexual misconduct with her father’s butler and chaplain!

References Ives, E. The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn, 2004. Sander, N. The Anglican Schism. Warnicke, R. The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn, 1989. Weir, A. Mary Boleyn: ‘The Great and Infamous Whore’, 2011. http://fr.topic-topos.com/tour-danne-boleyn-briis-sous-forges

Great article, Natalie! Love to think about what might have gone on in France with Anne. What she might have learned by example and experience. THanks!