Today’s post is a fascinating article by Katherine Marcella about the Mary Rose and its connection to Henry VIII’s sister, Mary.

I love having such talented readers who are willing to share their interests and expertise with us all. Thank you Katherine!

Mary Rose: The Princess and The Ship

A guest post by Katherine Marcella

Everybody knows the pride of Henry VIII’s war fleet, the Mary Rose, was named after Henry’s sister, Princess Mary Rose. Right? Well, almost, but not quite…

When Henry VIII came to the throne in 1509, he foresaw a threat to England from the powerful fleets of France and Scotland and immediately began shoring up England’s navy which had not been a priority during his father’s reign. He made a half-hearted attempt to diguise his efforts by claiming his new ships were merely pleasure vessels for the use of his family. It’s doubtful he fooled anybody, but among the first ships to be completed were the Henry Grace a Dieu, Catherine Pleasaunce, Peter Pomegranate — and the Mary Rose.

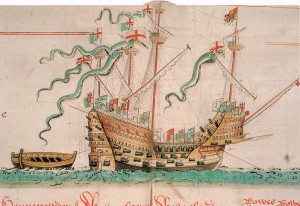

Her story is as murky as the waters of the Solent that hid her for 437 years. There is no extant documentation of her design. Construction may have begun as early as 1509 and documents from 1509 and 1510 show authorizations of construction materials for the building (most likely in Portsmouth) of a large ship that was eventually towed to London for final rigging and outfitting before joining the navy as a full-fledged combat ship. Even this early she or possibly another ship – as I said, it’s extremely murky — was being listed in documents as the Mary Rose (or Maryrose or even Marie Roze). She saw service as Lord High Admiral Edward Howard’s flagship in 1512 and 1513 in a combined English-Spanish-Empire campaign against the French.

By early 1514 the political winds had shifted. King Ferdinand of Spain and the Emperor Maximilian conspired behind Henry’s back to arrange a separate treaty with the French against England. Henry was livid. He started immediate negotiations with the newly-widowed Louis XII of France for a marriage between Louis and his own beloved younger sister, Mary Tudor, then around seventeen. By July, 1514, the agreement with Louis was secured, and Henry was ready to break Mary’s long-standing engagement to Prince Charles of Castile, the grandson of both Ferdinand and Maximilian. Securing Mary’s agreement to this was another matter.

Mary Tudor was an unusual princess in an age that cared little for the personal feelings of royalty, male or female. As a child, she was betrothed to the younger Charles in 1507, a betrothal firmly anchored in politics. The negotiations waffled on for years: They should marry now. No, they should wait. The terms aren’t good. Perhaps this isn’t the best match we could get. Perhaps we should discuss this further. The result was that Mary wasn’t married off early as her older sister Margaret had been. She remained in England and had free reign at her brother’s court.

She shone brightly there. As her brother’s preferred dance partner in court frivolities, she came to the attention of virtually all the ambassadors to the English court whose collective description of her was middling tall, blonde, stunningly gorgeous, and unbelievably charming.

Mary was not unduly unhappy at the dissolution of her betrothal, but neither was she interested in marrying the elderly king of France. Apparently she was won over when her brother promised her that after Louis’s death, she could marry as she pleased.

But the marriage to Louis was short-lived, lasting only about ten weeks. In poor health even before the marriage, he died on January 1, 1515. His new widow’s immediate concern was to avoid being married off by either the new French king, Francis I, or her brother. Both were eager to use her as a pawn in the chessboard of European politics. Tudor that she was, Mary played them off against each other. To Henry she merely promised she would not let Francis choose a husband for her. To Francis, she was a bit more forthcoming, admitting that the man she was in love with — the only man she would ever marry — was Henry’s close friend, Charles Brandon, the Duke of Suffolk.

Francis was disappointed, but somewhat mollified by the thought that Henry was going to be equally thwarted. As for Henry, he very conveniently sent Charles over to negotiate the return of the dowry and escort the widow home. It’s hard to know for certain what Charles and Mary had planned beforehand, but they secretly married almost immediately in Paris. I’ve always thought they decided it would be easier to obtain forgiveness than permission, and presenting Henry with a fait accompli would take away any temptation on his part to try to change Mary’s mind about another royal marriage.

By April of that year, they had resolved the dowry issue and obtained permission to return to England. Henry met with the newlyweds near Dover and, just to make certain there could be no legal objections raised over a marriage in France, he arranged for them to be married again at Greenwich on May 13, 1515.

If the Mary Rose had indeed been named after Mary Tudor, it would have been only natural for that ship to take Mary and her entourage to France or Mary and her new husband back to England. But that doesn’t seem to have been the case, and after early 1514 there is no mention of the Mary Rose until the autumn of 1518 when she and several other ships were laid up for caulking.

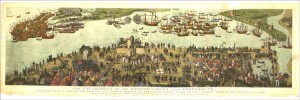

During this time another ship came to be associated with Mary Tudor Brandon. On October 29, 1515, this ship was sailed to Greenwich where amid many prayers and much music, Katherine of Aragon christened her the Virgin Mary. The Venetian ambassador, who was present and described the ceremony, stated that everybody immediately began referring to her as the Princess Mary in honor of Henry’s sister who also attended the ceremony. A royal banquet on deck followed, and Henry, a gold whistle around his neck, then proceeded to personally steer the ship down the Thames.

I find it odd that there would be two ships named after the same person, especially in such a short time span. That more than anything else leads me to believe the Mary Rose was not named after Mary Tudor — at least initially.

I think there is an outside chance that the ship known as the Princess Mary may actually have been the Mary Rose which isn’t recorded as having ever had a christening. Christening rules seem to have been very loose, with no set time frame in which the ceremony should be conducted, so it’s not out of the question that Henry might have decided to hold a splashy ceremony for one of the largest ships in his navy and honor his sister at the same time.

I could find nothing in the known history of the Mary Rose to contradict this possibility. Nor could I find any further mention of a ship known as the Virgin Mary or the Princess Mary. This would be an interesting project for anybody with better access to Tudor maritime records than I currently have to investigate. I would love to see what turns up.

Even if they aren’t the same ship, it’s possible the elaborate ceremony and the similarity of names may have blurred in the public mind and created an association of Mary Tudor with the Mary Rose where one had never really existed.

Through the years the Mary Rose eventually saw further action against the French and possibly against the Scots until her sinking in the Solent at Portsmouth Harbor on July 9, 1545.

As for Mary Tudor Brandon, she died in 1533, her association with the ship already firmly established by her death. But was her name really Mary Rose? No. Middle names were almost unheard of in Tudor times and were completely unheard of for royalty. There is no reference or documentation during Mary Tudor’s lifetime that would even suggest a possibility she had a middle name.

I haven’t been able to determine exactly when she was first called “Mary Rose”, but I believe it is a 20th-century phenomenon. The earliest biography I have of Mary is Mary Croom Brown’s Mary Tudor, Queen of France, published in 1911, which does not call her Mary Rose nor does it even mention a possible connection between the Princess and the ship. Other biographers also seem to have been careful in this respect, but popular literature is another matter. I haven’t read every romance novel about Mary, but I just gathered together all the ones I do have and checked them. Every last one of them calls her “Mary Rose”.

I can’t say I really blame them. It’s a very pretty name that they would certainly want to associate with a pretty princess. Combine that with the serious attempts to salvage the Mary Rose that began in the 1970’s and brought the ship into the public consciousness and the renewed interest in the Tudors that has shown itself in numerous books, television programs, and movies. The result is almost inevitable. In addition, the name is very practical. It serves to distinguish Mary from Mary Tudor, her niece and namesake. Google “Mary Rose Tudor” and you will get numerous questions and discussions on Tudor sites that refer to her by that name.

For better or worse, where once there was a 16th-century ship that came to be associated with a princess in the popular mind, now there is a princess who is being renamed after that ship in the 21st-century mind.

On the Tudor Trail is trying to raise much needed funds for the Mary Rose Appeal and needs your help! Read full details of how you can contribute here.

There’s an interesting little side note to this article that I didn’t include because it was off-topic, but I think it deserves to be known. Almost as soon as the ship sank, recovery efforts were discussed. They seemed to have had the technology at the time to recover the ship if she had sunk in an upright position. But she didn’t. She sank starboard side down into the mud. That was bad news for the Tudors, but good news for us, as it meant so much of her was preserved for recovery 400 years later.

But who did Henry VIII put in charge of the recovery efforts? Charles Brandon! As he always did for Henry, Charles gave it his best effort, but was unable to do successfully complete this mission. He died a month after the Mary Rose sank.

In C. J. Sansom’s latest novel, Heartstone, the sinking of the Mary Rose is depicted in detail. It must have been awful for those aboard. I enjoyed your posting which gives great background information. Thank you.

Thank you so much for a truly fascinating read!

Wonderful!!!

Thanks,

Marianne

I really enjoyed your posting and the details about the ship and Mary Tudor. That added piece about historic efforts to retrieve the ship is interesting.

Thanks!

Enjoyed posted article. I have read several books and journals on the Mary Rose and seen several documentaries on the ship. Although there is very little evidence to support the idea that the ship was called after his favourite sister, it is a romantic and sentimental idea and as a romantic I would like to think that it is true. Henry was very fond of Mary; she was very close to him. It is very possible that she was (the ship) was named after Henry’s favourite sister and at the time that she was launched, he was a young king and his romantic side had not yet been destroyed by life and the need for a male heir. Scholars on the other hand, believe that it is more probable that the ship was in fact called in honour of the Virgin Mary, who as the Star of the Sea, was called upon to protect sailors and Henry, Katherine and his sister had a personal devotion to the mother of Jesus. As a romantic, however, I still go with her being named for his sister.

Since Henry VIII’s mother was Elizabeth of York who’s symbol was the white rose, maybe that was the reference for the Mary Rose?