This story was a place getter of the original Tudor Ghost Story Contest (then known as The Tudor England Ghost Story Contest). Permission was then kindly granted to Wendy J. Dunn to publish these stories. If you are the author of this story and rather not have it published here, please just send me an email. I hope this inspires you to get writing, remember that this year’s competition closes on 1 October, 2015.

The Maid’s Tale By Geoffrey James

A fire blazes in the Great Hall’s central hearth, but still the winter wind sneaks somehow in, a strong draught playing tug and war with a nearby ajar door. Even though the lure of bed will beckon soon, knowing it’s warmer around the roaring fire makes every one happy to stay, drink mulled wine and talk. Then the conversation lulls – and in this quieter time some one offers to tell a ghost story. Looking up from stroking the sleeping spaniel on her lap, Mistress Gwenda’s eyes almost glow from the light of the fire. She glances around at her companions.

“I would like it well if all of us tell a tale…”

It was at that point that the elderly maid – who had been waiting patiently on her mistress – spoke up:

“A pleasure it may be to hear the stories that you gentlefolk have told and to be sure the hairs on the back of my neck have stood up at the mere thought of these things. Be that as it may, the tales you tell are, for the most part, of the second and third hand, and I’ll wager that not a one of you has ever so much as heard or seen a ghost. But, if my lady will allow it, I will undertake to tell you a true tale, something that I saw with my own eyes and heard with my own ears.”

The company, which at first had been surprised (and not a little offended) at this outburst from a servant who had hitherto remained silent, were now anxious to hear her story and begged her to continue.

She told the tale thus:

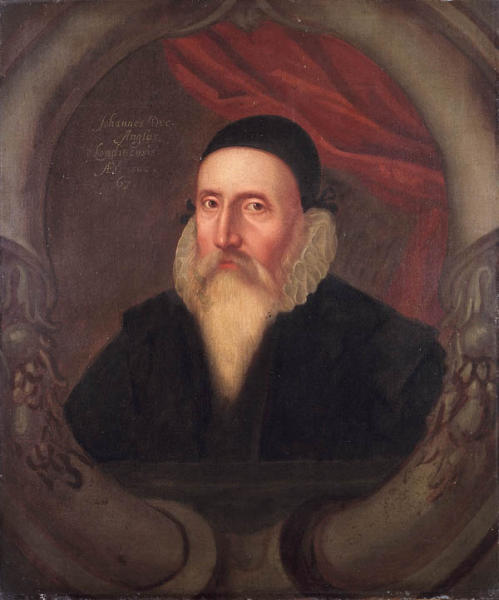

“My name, as some of you know, is Ellen Cole and I was, for many years, the maid of the famous John Dee. Aye, you may well start when you hear that name, but I tell you now that many of the foul tales told about him are untrue. Despite what you might have heard, he was (and if, for ought I know) a good and holy man, though he knew much about astrology and mathematics. He was a great friend of the Queen and of the late Lord Leicester – god rest his soul – and many was the time that a great lord or lady came to have their nativities drawn.

At that time, we lived in a house by the river in Mortlack and never did you see such a strange place. There were, oh!, thousands of books in the place, all scattered here and about, and in his special rooms there were brass instruments and globes with stars inscribed upon them. I was not allowed to touch them, but many was the time I looked at the signs and sigils on the globes and wondered what they meant.

It must have been around ’80, for it was not long after Drake returned, a strange man came to the house as the guest of a friend. He was a dark one, with a black beard that ran down his chest like great swath of mourning velvet. I was serving at table, and so I heard some of their conversation.

This man – his name was Edward, I think – told the company that he was plagued with visions of spiritual creatures, so much so that sometimes he could barely sleep for all the noise and trouble that they caused him. Most of the company, including Dee’s wife – who was both frivolous and vain – laughed as if he had made a jest, but the master did not laugh with rest, but simply peered at this Edward, as if he wanted to learn more. But the conversation moved on and no more was said on the matter.

Over the next few days, though, this Edward became a something of a regular visitor in the house, spending many hours with the master, closeted away in the study. At first we thought nothing of it, because the master was always receiving and consulting with visitors, but when George, the master’s groom,went to fetch him out one evening (for another visitor had arrived), he heard something behind the locked door that made him wish – as he put it – that he were a thousand miles away. It was, as he put it, a kind of croaking sound, like that of a frog, but he swore that ‘there were words in it.’

After this, nobody was willing to disturb the two of them when they were closeted away, but like the cat in the fable I was curious to learn more.

One night, when the rest of the house was asleep, I heard a knocking upon the front door of the house. I went to answer it but when I came to the stairs, I saw, in the light of a candle which he held in his hand, the back of the master as he went to answer the door himself! I followed quietly and, from the foot of the stairs, saw the face of this Edward framed in the doorway.

I scurried upstairs, lest I be seen. I tried to sleep, but the thought of the two of them, alone in the master’s study, was like a spiced cake that has been forbidden to a hungry child. Finally I could bear it no longer. I threw my cloak around my shoulders (for I did not know how long I would be out of bed) and crept, tiptoe, through the stacks of books, and the brass instruments, with naught but the moon’s feeble light through the narrow windows to guide me.

There was a light beneath the door of the master’s study, though, and as I approached the door, I forced myself to breath quietly, for I had no desire to be discovered spying upon my master. I knelt quietly by the door and pressed my ear against it.

The master was speaking, but not in any voice I had ever heard him use. He was reading what sounded like some sort of prayer, but the words were sometimes garbled, as if they were in some different tongue. Sometimes he would repeat words that I can still remember. It went: ‘Come! Appear before us! I summon you by the name of God!’

I listened to this for many heartbeats, wondering what the other man was doing. I was about to return to my room, when I heard a long, low moan, rolling underneath the master’s chanting. Was he ill? I thought to myself.

The master’s voice grew louder, more insistent. ‘Come! Appear before us!’

Another long moan and then, in the midst of the moan, there was a voice, but it wasn’t like any voice I had ever heard before. It sounded as if it were coming from below the house, it did, but it was the words themselves that put a chill into my bones. It said, slowly, pausing between each word:

‘I HAVE COME!

The master stopped his chanting and I heard a rustling noise, as if somebody were shuffling some papers about. Then the master spoke, this time in a normal voice, but hushed, as if he were himself frightened.

‘Who are you?’ he asked.

Then the deep voice again.

‘I AM!’ it began, and then there was a word that I did not understand. As I attempted to hear the better, I pressed my ear more closely to the wood and then, to my horror, the door – which had not been locked or latched – drifted open, revealing the entire contents of the room.

The two of them were sitting around a square table, draped in colored cloth, with a candle propped at each corner. A great book was open in front of the master, and he was holding a pen, its tip wet with ink. I took in all of this in the blink of an eye, but then I saw the other man and the thought of everything else – even the fear that the master might punish me – vanished from my mind. He was slouched down upon a low chair, his head thrown back, his mouth open, the candles casting black shadows where his eyes should have been. The jaw was not moving, but there was a murmuring voice coming from his throat. I cannot explain why it seemed this way, but it was as if something else was in his body, forcing it to speak.

The master looked up at me, and angrily waved me away. I departed at once, catching a glimpse of the master out the back of my eye as he shut and latched the door. The master spoke to me sternly the next day, telling me that I would be dismissed if I ever spoke of what I had seen, and charging me solemnly to never intrude again upon his ‘experiments’ – as he called them.

It was not long after that that I left his service, for I did not feel comfortable living in place with such strange goings-on. As for my master, why, he’s left for Europe, they say, in the company of a Polish count and with this Edward fellow, and it looks likely now that nobody will ever hear of the two of them again.”

With this, the maid fell silent, while the rest of the company pondered the tale that she had told. The mistress called it “a passing strange tale,” but the general judgement of the company was that it lacked all the requisite elements of a really good ghost story, having no rattling chains or smoky apparitions. Thus, when the company finally voted on who had told the best story, the maid’s tale was not even included in the tally, but I do not know whether that was because they found the tale lacking or merely because the tales had been told by a servant.

Geoffrey James is the author of the non- fiction book ‘The Enochian Magick of Doctor John Dee,’ available from Amazon.Com.

Latest Comments