I am delighted to welcome Barbara Gaskell Denvil to On the Tudor Trail!

Born in England, Barbara grew up amongst artists and authors and started writing at a young age. She published numerous short stories and articles, and worked as an editor, book critic and reader for publishers and television companies.

With a delight in medieval history dating back to her youth, Barbara began to research the wicked King Richard III, but quickly discovered the fascination of looking past Tudor propaganda to discover the real man. She now writes principally on this era, setting her fiction in 15th century England.

Barbara’s novels include Blessop’s Wife, Sumerford’s Autumn and Satin Cinnabar.

Barbara joins us today with a guest post about Tudor London.

TUDOR LONDON

By Barbara Gaskell Denvil

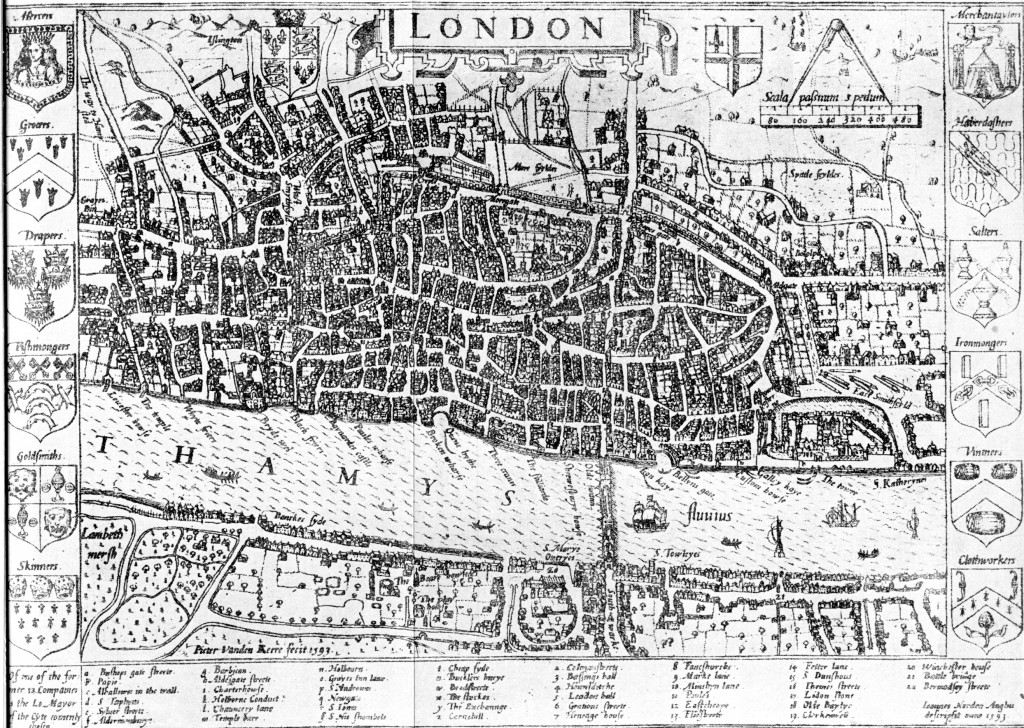

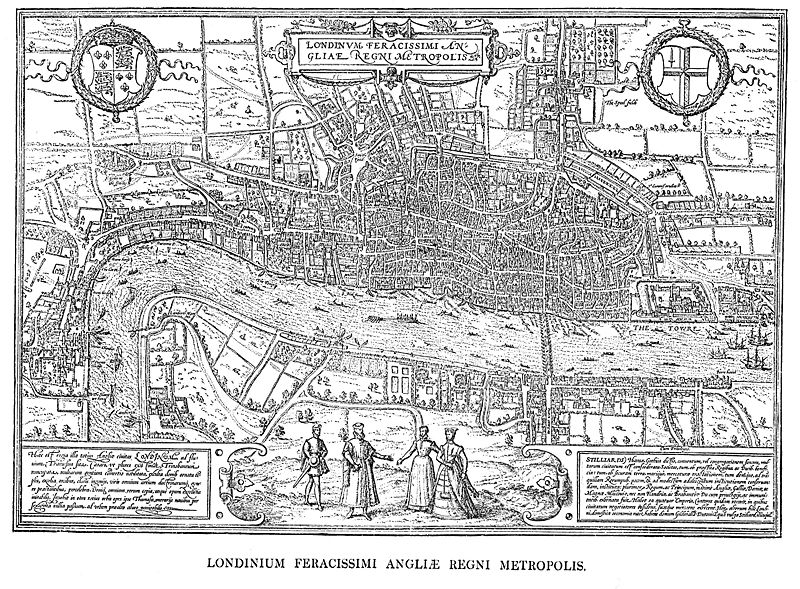

The City of London was founded in Roman times, although an indigenous settlement already existed on the banks of the Thames. It was for fortification against the furious hoards of the vanquished, that the great Roman walls were built to keep the inhabitants safe. Those walls stood long past the Roman occupation, and during Tudor times the city was still nestled snug within those great stone arms. Immediately beyond was the Ditch, which, in spite of various attempts to clean it up, remained a noxious depository for rubbish, sewerage and mud. Standards of cleanliness amongst the people of that era were not as terrible as some now suppose, but certainly the stench from the Ditch must have swept full on the wind. Just a mile square, the city was large for its time, and contained all the luxuries a citizen might need. The great central road of the Goldsmiths was internationally famed, while other roads housed the several busy markets, warehouses for storage and imports, vintners and brewers, ports large and small, grand houses, slums and a multitude of both taverns and churches. The Palace of Westminster was some distance outside the city walls due west, but the city’s East Minster was the Cathedral of St. Pauls. Within the walls there was the beautiful, the ugly, and the dangerous.

So close your eyes, inhale deeply, breathe in and savour that smell, and hear those footsteps.

Clip, clip, clip. Flat soled boots on wet cobbles, and the sounds of falling rain collecting in the central gutter, washing away the accumulated grime. Small noises are muffled. There is only human sound on a human scale. Birds, the wind in the bushes along the riverbanks, the people hurrying back home to warmth and shelter. Someone is singing in an ale house nearby, and someone else is scolding a stray dog begging in the alley. No buses, no roaring traffic, nor thousands of people rushing back to work. Everything is small, friendly, and quiet, like whispers in the night.

And now it is also growing dark. Narrow roads wind and turn sudden corners. High walls shut out the moonlight. Alleys and lanes are unpaved, and in the rainfall the beaten earth turns to mud. Along the main roads, the cobbles are slippery but in the alleys there is just the squelch of boots in sludge. Someone on horseback races past, you are pushed to the wall and your heart pounds. The hooves splash up mud into your face. The rider’s oiled cape slaps against you. So you wait a moment to catch your breath, then trudge on as the galloping echoes disappear into the darkness.

A candle flickers behind the greenish smear of thick glass mullions. Further along there is the brighter flare of a lantern behind another window, but it is quickly extinguished to conserve oil. Candles, even the cheaper tallow-made, are expensive, oil more so. Everything must be conserved when possible. This is no world of commercial abundance, expected obsolescence or casual waste. So when the sun sets and the dark shadows loom, most people prepare for bed.

Once the rain turns to sleet, there are few who will leave their homes, and the shops shut early. Their counters, made from the opening flap of the wooden window shutters, are pulled back indoors and the shutters are raised and bolted. You can hear the echoes all along Goldsmiths’ Row – bolts pushed home and doors shut and locked. Craftsmen usually sit in their open doorways when the businesses are open, displaying their wares and the workmanship, ready to attract and speak with customers. But now all is quiet and closed as the rain pelts down. Inside the shopkeepers light their fires and balance the iron pots on the trivets over the flames to warm the remaining pottage for a quick supper before hurrying upstairs to bed.

Now it is nine of the clock on a cold winter evening, and through the heavy rain, church bells can be heard. It’s the deep resonating chimes from St. Martin-le-Grand that many folk are waiting for. As the echoes ring out, the gatekeepers call for the last travellers to make haste, as the gates will now be closing for the night. Ludgate, Newgate, Aldersgate, Cripplegate, Moorgate, Bishopsgate, Aldgate, and finally the gate at the southern end of the Bridge where the traitors’ heads, tarred and grotesque, are spiked high above, warning trouble-makers to keep the law. Every gate swings heavy until shut and locked. And now the city is closed for the night, and no one, unless they swim the cold river waters, will enter or leave until the following morning.

Utter silence falls, even heavier than the rain. The slurp of water through the gutters, the constant patter of raindrops on the Thames, the splash of a swan settling for the night, and the stealthy exploration of a stray dog hoping for shelter. There will be few other sounds until the Watch passes, marching the main thoroughfares, the flare of their torches held aloft and hissing in the rain as they look for any apprentices out past curfew, or other citizens with burglary or mischief on their minds. But once the Watch has passed, the great silence once more engulfs the city. The stars blink out above the church steeples, the river tide ebbs, and London sleeps.

This is a world that haunts my dreams. It inhabits both my imagination and my books. All my historical novels take place more or less within the boundaries of London’s great walls, but it is not all peaceful. There’s political revolt and crime, abduction, arrest and torture, execution, struggle, courage and great romance. Against London’s shadows, my varied and various characters battle out their lives in medieval and Tudor England.

SUMERFORD’S AUTUMN and SATIN CINNABAR are both romantic adventure mysteries set during the dawning of the Tudor period. BLESSOP’S WIFE takes place a little earlier, around the death of King Edward IV. But all are vivid with the breath of the old city, and the ordinary people who strived there.

Wonderfully evocative, thank you for sharing.

So evocative. I was there! Beautifully written, described, Thank you so much!