Stitches in Tudor Time: A three-part series by JoAnn Spears

Part Three

We, Hermia

‘We, Hermia, like two artificial gods,

Have with our needles created both one flower,

Both on one sampler, sitting on one cushion,

Both warbling of one song, both in one key,

As if our hands, our sides, voices and minds,

Had been incorporate.’

From A Midsummer Night’s Dream

To bee or not to bee

A bee, or gathering together of people for a purpose or project, is famously associated with quilting done by women on the American frontier in pioneer days. Helena’s words from Midsummer, however, remind us that needlework bees go back much further than that. Clearly, even in Shakespeare’s day, the image of women bonding together over stitchery was a familiar one.

We also have Shakespeare to thank for the metaphor of ‘strange bedfellows’. There were surely none stranger in the Tudor era than Mary Queen of Scots and Bess of Hardwick.

Mary Queen of Scots, a Tudor cousin and the Catholic contender for the throne of England, spent her childhood in France and was its queen for a brief time. A young widow, she returned to her native Scotland to take up the reins of government. That did not go well. A few short years saw a disastrous marriage, her husband’s murder, and a remarriage under bizarre circumstances that was her political undoing. She eventually refugeed to England, where she caused almost as much turmoil as she had in Scotland. Her Catholic presence in England was a direct threat to the Protestant Queen Regnant, Elizabeth I.

To handle the Queen of Scots situation, Elizabeth called upon a woman as solid and sensible as Mary was unpredictable and imprudent: Bess of Hardwick.

Bess married her way to prominence in the Tudor world–several times–and was Countess of Shrewsbury when Elizabeth called upon her to be Mary’s wardress for what turned out to be Mary’s virtual house arrest in England.

Bess was in a tough spot. She needed to handle Mary sternly enough to please Elizabeth’s security-conscious government. It also behooved her not to treat Mary too harshly; in the event of Elizabeth’s death, Mary could well become Queen of England one day. How to establish the right relationship with her ‘guest’? Bess and Mary apparently figured it out together over the needlework frame and the embroidery hoop.

Busy bees

Mary would remain in the custody of Bess and her husband, George, for about 15 years. They owned numerous residences in the midlands, and Mary would be shuffled from one to the other, and back, over the years. From 1569 to 1571, early in Mary’s imprisonment, she and Bess spent much time together at Bess’ Chatsworth House. It was here that Mary and Bess worked on textiles that are included in what are now known as the Marian and Oxburgh Hangings.

Mary and Bess worked many emblems, or squares, of needlework. It has been suggested that Mary preferred these smaller projects as they would be easy to pack and take away with her should the opportunity for escape present itself.

Bess and Mary for the most part stitched these pieces in tent stitch on canvas, a technique similar to what we would call needlepoint or petit point today. This is in contrast to much of the stitchery of the day, which emphasized elaborate, complicated stitches for their own sake.

The inspiration for many of Mary’s and Bess’ emblematic pieces came from design books. Some of the illustrations in these books were copies or interpretations of images from naturalists Claud Paradin, Conrad Gessner and Pierre Belon. Depictions of New World flora and fauna likely opened up a fascinating world to the isolated Mary.

Pierre Oudry, a professional embroiderer employed by Mary, probably drew her chosen designs onto needlework canvas and outlined them in black silk for the ladies to execute in tent or cross stitch. Mary monogrammed her pieces with the initials M and A and the Greek phi. Bess monogrammed hers ES. Some of these small needlepoint pieces were assembled into panels by securing them onto green velvet. The purpose these panels were put to at the time of their creation is unknown. In the 17th century, the panels were sewn into the wall hanging, bed curtains, and valance that now are on long-term display at Oxburgh House.

The buzz

Although Mary and her ‘hosts’ got along well for a long time, the relationship eventually deteriorated. Bess’ strong personality, Mary’s manipulating ways, the Earl of Shrewsbury’s soft spot for Mary, and the stress of a difficult situation over a long period of time all may have played a part. Mary was eventually removed to the custody of Amyas Paulet, tried for plotting to overthrow Elizabeth I, and executed. Bess and her husband were married but separated at the time of the Earl’s death.

Busy bees

Mary and Bess are said to have produced over 300 small pieces of stitchery over the period of Mary’s detention.

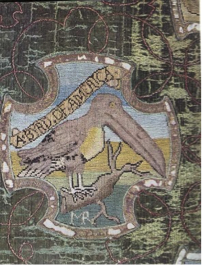

A Byrd of America is probably a toucan. Mary may have had an interest in things avian; some of the items she left in Scotland when she abruptly departed included feathers and a beak from a Brazilian bird.

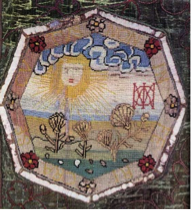

Marigold turning to the sun features some New-World flowers and the motto of Mary’s former sister-in-law, Marguerite, which translates to ‘its strength draws me’.

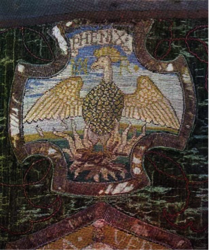

The ‘Phenix’ was an emblem of Mary’s mother, also named Marguerite, who reinvented herself after more than one setback. The image calls to mind Mary’s own motto as a Catholic martyr, ‘in my end is my beginning.’

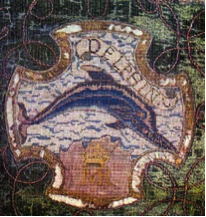

The ‘Delphin’ is likely a tribute to Mary’s first husband, the one-time Dauphin, or Prince, of France.

Mary’s dark side emerges in The hand and the pruning hook. This piece was a gift to the Duke of Norfolk, with whom Mary was conspiring to affect an escape, a marriage, and the seizure of the throne of England from Elizabeth I, the Virgin, and childless, Queen. The symbolism of an unfruitful branch being cut off to facilitate the growth of a new and more fruitful and desirable one would not have been lost on anyone in the symbolism-conscious Renaissance.

Jupiter, most likely, was Mary’s fur-baby. (At least, that is what I assumed when I wrote him into ‘Seven Will Out.’)

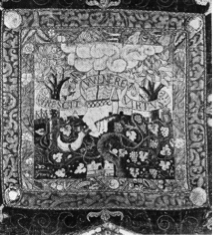

It could be called ‘A lot going on’. This piece was probably stitched at either Tutbury or Sheffield, two of the manor homes Mary and Bess resided in. Included are feathers, a rock jutting out of the sea, the arms of England, France, Scotland, and Spain, sea monsters, a ship, and words that translate ‘sorrows pass but hope survives’. This is dated to a later period in Mary and Bess’ relationship, circa 1585.

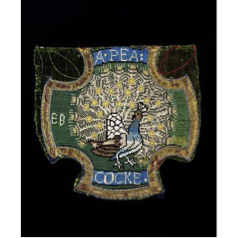

A Pea Cocke, initialed EB, is a surprisingly fanciful piece by the practical-minded Bess of Hardwick. It was likely completed at Sheffield, circa 1570.

A bee in her bonnet?

The most touching of these works, a single cruciform piece by Mary that resides at Holyrood House in Scotland, is known as A Catte.

The cat in question is, like Mary’s nemesis, Elizabeth I, ginger. It sits intently watching an unfortunate mouse. It is tempting to think that the work may have been a way for Mary to work out the frustration of being a captive at the whim and mercy of a more powerful adversary than she.

Such is the fascination of Mary and her story that a reproduction of A Catte is available for stitching by the modern needleworker and history buff, ideally with a frenemy to replicate the full Mary-and-Bess experience.

An assessment of all of Mary’s extant needlework was completed in 1986 by Margaret Swain.

Thank you for joining me for stitches in Tudor time!

JoAnn Spears, author

Six of One, a Tudor Riff

Seven Will Out, a Renaissance Revel

Latest Comments