I am delighted to be hosting day 13 of Dr Sean Cunningham’s blog tour for his latest book, Prince Arthur: The Tudor King Who Never Was. Sean has written a fascinating guest article for us, about Arthur Tudor’s funeral.

Prince Arthur’s Funeral: Ceremony, Despair and Shifting Politics in 1502

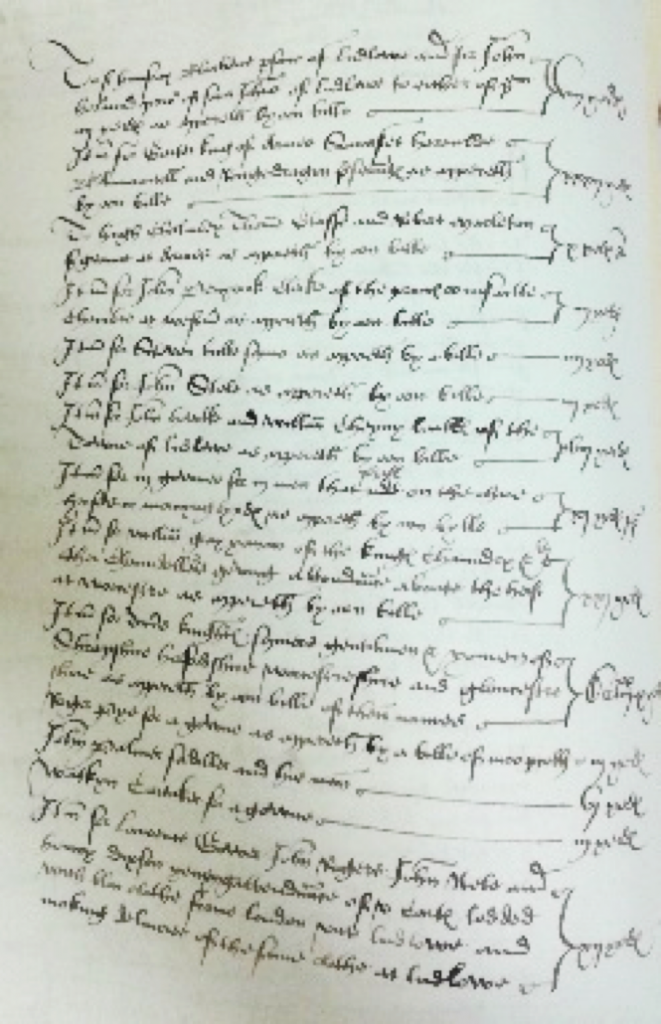

Unlike many other of the main events connected with Arthur’s life, the herald’s eyewitness record of his funeral ceremonies and procession from Ludlow to Worcester is matched by full financial records in the king’s exchequer, which paid for everything. Together, the detail supplied provides an amazing insight into late medieval royal funerals and, more specifically, how Arthur’s network of friends and officials had taken shape.

Very quickly after death around 7pm on 2 April 1502, Arthur’s corpse was disembowelled, embalmed and dressed with as many sweet spices as could be obtained in Ludlow. Speed was of the essence since Arthur was thought to have died from a contagious disease. Arthur’s deep connection to Ludlow was shown by the decision to hold his funeral in the marcher region. Although fatally ill, the prince still had time to ask that his heart was buried in the Ludlow castle’s St Mary Magdalene chapel.

Arthur’s coffin was covered with a tight fitting black cloth onto which was sewn a white cross. Up to eighty people who had received alms from the prince on Maundy Thursday sat guarding the coffin on rotation; holding torches that burned night and day until St George’s Day, 23 April. That delay allowed arrangements for the rites and ceremonies to be made.

As soon as Arthur had breathed his last, messengers had been sent out across the region with the terrible news. One of them covered the 160 miles to Greenwich Palace by the early morning of 5 April; a little over two days of travelling to break the devastating news to the king, queen and Arthur’s brothers and sisters.

The sweating sickness epidemic remained too great a risk to the royal family to allow any of them to travel to attend the funeral rites. Arthur would be buried as a great regional nobleman of royal blood, but without his close family in attendance. The three-week period between his death and interment at Worcester provided time for all preparations to be rushed into place; another indication that his death was a sudden shock to everyone.

Funeral robes and hoods were required for over two hundred people from Arthur’s household and the Council of the Marches.

Chandlers, carpenters, sawyers, and painters worked constantly over the days between Arthur’s death and the funeral. Their raw materials had to be supplied; which included all string, rope, ironwork to bear the weight of the banners and torches; wood, ladles and cauldrons for melting wax; nails, buckram and other backing cloth. The urgency of the task was suggested by the hiring of moulds for castings for the decoration of the hearse. Gold and silver leaf, coloured paint, and over 1500lbs of wax were bought from other traders at Worcester. The crown’s purchasing power must have put severe pressure on local suppliers and what could not be found locally was sought in London, such as hundreds of yards of mourning cloth for over two hundred people linked to Arthur’s household and council.

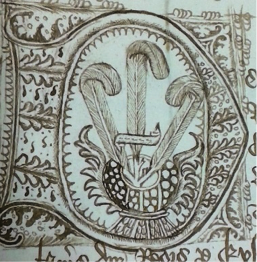

Henry VII’s painters, headed by John Fligh, prepared four holy banners that would accompany Arthur’s corpse – the Trinity, the Patible Cross, a banner of Our Lady, and one of St George. They also made others of royal heraldic arms, and eleven long streamers or bannerells that presented a mixture of familiar heraldic imagery and the traditional, ancient and mythical symbolism that had been associated with Arthur: Cadwallader and Brutus linked the prince to the heroic kings and original founders of Britain. The Welsh arms confirmed that Arthur carried forward his father’s claim upon Welsh loyalties, while the representation of Irish arms and those of the French duchies of Normandy and Guyenne also suggest wider imperial ambitions. Arthur’s battle standards of the Cross of St George with a White Hart, and an image of St George with the prince’s ostrich feather were also remade.

On 23 April, St George’s Day, the coffin was moved to the hall of the castle where it was put on trestles in preparation for a funeral procession through the town of Ludlow to the church of St Laurence. Thomas Howard, earl of Surrey was the chief mourner. This position of honour showed how completely he had been rehabilitated after fighting on Richard III’s side at the battle of Bosworth.

Surrey was followed by the earls of Shrewsbury and Kent, in black jackets and hoods, and then by lords Grey of Ruthin, Dudley, Grey of Powys and Sir Richard Pole, Arthur’s chamberlain. The sons of other lords also present can be identified as some of Arthur’s friends. Anthony Willoughby, Edward Howard, Robert Radcliffe and John St John steadied a canopy of purple damask over the moving coffin. The eighty poor mourners then joined in, each carrying a burning taper.

In the church the coffin was laid in the choir as a funeral mass was led by the bishop of Lincoln, William Smith. After the service Arthur’s body remained in the church while the chief officers and mourners retired to the castle. A vigil over the corpse was held all night. Masses and doles were repeated the next day, with a prominent role given to the Spanish Ambassador, Pedro de Ayala and the town officers of Ludlow.

25 April was a horribly wet and windy day to travel the twenty miles from Ludlow to Bewdley. Although fine black velvet cloth of gold covered, wrapped or shielded everything on the hearse, the casket itself had to be protected from the elements by another waxed black cloth. The passage of hundreds of people also turned the roads to mud. The emotionally draining journey also became physically exhausting. When the cortege did reach Bewdley, four labourers were paid to work through the night to clean the horses, their trappings and the wheels of the hearse.

From Bewdley, Sir Richard Croft and Sir William Uvedale, steward and controller of Arthur’s household, rode ahead directly to Worcester to see to the burial arrangements in the cathedral. They closed the gates of the city so that everything could be prepared without distraction. The procession followed more slowly. The members of the orders of friars of the city met the corpse at the north gate and censed the coffin as it passed. 120 new torches were supplied and fresh draught horses brought to lead the hearse through the streets to the cathedral.

Arthur’s body was welcomed and moved through to the chancel, lit by almost 400 candles in massive candelabra. The abbots and priors of all the regional houses were also present with very many of their monks and nuns. With well over a thousand people involved, and much of the rest of the city brought to a halt by the spectacle, the funeral must have been a magnificent sight; unrivalled since King John was buried there in October 1216.

The following day saw the most solemn and emotional part of the entire funeral period. The body was watched all night and by eight o’clock in the morning the congregation reassembled for singing of masses of Our Lady, the Trinity and Requiem, in a repeat of the ceremony at Ludlow. During the Requiem the offerings began to be made.

All mourners offered the mass penny. Then two heralds brought forward Arthur’s rich embroidered coat of arms to the earls of Shrewsbury and Kent. Lords Grey of Ruthyn and Dudley received the shield from the heralds, Lord Grey of Powis the sword, pommel forwards, Sir Richard Pole the helm and Lord John Grey the crest.

Then a group of Arthur’s household officers escorted the Man of Arms into the middle of the choir. The Man was Lord Gerald FitzGerald, son of the 8th earl of Kildare. He rode the prince’s courser and wore Arthur’s full armour. The horse, itself an offering, was fully equipped with a trapper embroidered with the prince’s arms and Lord Gerald carried the prince’s poleaxe, head downwards. During the reading of St John’s Gospel, Sir Gruffydd ap Rhys passed the prince’s standard to the deacon of Worcester as another offering.

As the time approached to lay the body in the grave, the intensity of singing and prayers increased. At that point there seems to have been an eruption weeping from the congregation. The account says that ‘he had hard heart that wept not’. The chief mourners then made direct offerings of pall cloths to the corpse.

More anthems were sung by the whole congregation as the prelates gathered to cense the coffin. As it was laid in the ground the bishop of Lincoln, William Smith, started to say the prayers but could barely speak his words for crying. He placed a cross on the coffin in the grave and was the first to cast holy water and earth onto it. Arthur’s own herald, Wallington, took off his coat of arms and laid it onto the coffin. The chief officers of the household then demonstrated the end of their personal service with the prince by breaking their batons of office and casting the pieces in the grave.

The spectacular ceremony and the formal stages of mourning were still dependent upon the human beings involved being able to fulfil their roles. Since the clergy leading the service were as close to the prince as anyone else, shared grief must have put a strain on completion of the ceremony. Part of the sadness undoubtedly stemmed from a sense of what was now lost to the region and to England’s future.

For others, like Arthur’s friends Gruffydd ap Rhys, John Lord Grey and Gerald FitzGerald, his death represented an end to their route to the centre of power. Arthur’s household does seem to have been used as a training ground for royal wards of a certain age who were encouraged to form friendships with each other and with the prince. The account of the funeral reveals their main purpose, which was to form a tight-knit core of support to give strength to the foundation of King Arthur’s rule.

Some noble networks took longer to readjust to Arthur’s death. The Grey family, represented at the funeral by the branches of the earls of Kent and the lords Ferrers of Groby, had worked hard to move into the orbit of the prince as a way of maintaining close links to the crown. As the future of the Tudor crown shifted from Arthur to Prince Henry, those who had built strong links with the eldest prince were already on the back foot as his younger brother began to shape his own network before 1509.

It might be inappropriate to see the influence of families like the Greys as a precursor to the type of power-politics that becomes more familiar in the activities of the Howard or Boleyn families during Henry VIII’s reign. By the mid-1520s, the inability of the second Tudor king to produce a legitimate male heir allowed for a very strong element of sexual politics to revolve around families competing for access and influence over him. Nothing like that was obvious at Prince Arthur’s court.

Nevertheless, there must have been a common bond for that particular cross section of lords to have made the journey to Ludlow in April 1502 as a particular act of respect to Prince Arthur. That in itself suggests that they possessed a stronger connection to the prince’s life than others that were not there. Those people that jostled for close connection with Arthur were attempting to position themselves to be able to react to the way the world would turn when Henry VII died and their prince became king. Sadly for them, and perhaps for England, Arthur’s death changed the course of history once Prince Henry became the heir who would inherit the crown.

Book available from Amberley, Amazon and other online outlets and bookshops.

Author Bio

Dr Sean Cunningham, is Head of Medieval Records at the UK National Archives. His main interest is in British history in the period c.1450-1558. Sean has published many studies of politics, society and warfare, especially in the early Tudor period, including Henry VII in the Routledge Historical Biographies series and his new book, Prince Arthur: The Tudor King Who Never Was, for Amberley. Sean is about to start researching the private spending accounts of the royal chamber under Henry VII and Henry VIII for a new project with Winchester and Sheffield Universities. He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and co-convenor of the Late Medieval Seminar at London’s Institute of Historical Research.

Arther tudors life may have been short but I love him. He is fascinating