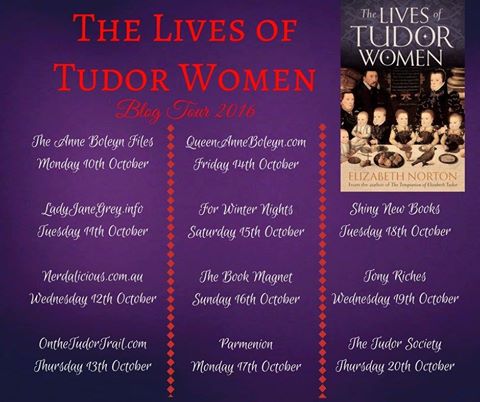

I’m delighted to be taking part in Elizabeth Norton’s book tour for her new book, ‘The Lives of Tudor Women’. To celebrate its release, Elizabeth has written a fascinating guest article about a day in the life of a Tudor woman. Enjoy!

A Day in the Life of a Tudor Woman

My new book, The Lives of Tudor Women, is a biography. It looks at the life of a woman, who was born in 1485 and died in 1603. She was a princess, a queen, a noblewoman, a merchant’s wife, a servant, a rebel, a Protestant and a Catholic. She was wealthy, she was poor. She married once, twice, thrice and not at all. She died in childbirth, she died on a burning pyre, she died at home in her bed. She spent most of her life in the house, and she left home when young and did remarkable things. She changed England and was celebrated forever, and she was forgotten, a mere footnote. She was all these things and more. She was a Tudor woman.

It is, of course, impossible to generalise with this Tudor Everywoman figure. Lives were always varied while the Tudor dynasty itself lasted more than one hundred years. Nonetheless, there were certain aspects of life that were familiar to all women and, as such, it is possible to go some way to reconstructing a day in their life.

It is, of course, impossible to generalise with this Tudor Everywoman figure. Lives were always varied while the Tudor dynasty itself lasted more than one hundred years. Nonetheless, there were certain aspects of life that were familiar to all women and, as such, it is possible to go some way to reconstructing a day in their life.

In the morning a Tudor woman woke in her bed. It might be gilded, with velvet bed curtains, or it could be a pallet or a mere rolled mat on the floor. Cecily Burbage who, in July 1492, was handed Princess Elizabeth – second daughter of Henry VII – to nurse, had probably been up caring for her charge for much of the night.

After her christening, the baby had been taken to join the royal nursery at Eltham Palace, alongside her brother, Prince Henry, and sister, Princess Margaret. All three were still young and each had their own nurses and rockers, who were employed to rock their cradles when they were tiny. Princess Elizabeth’s swaddled body might have been gently tied into her cradle by her rockers to ensure that she did not fall.

The bulk of the childcare fell to Cecily, who had left her own family to nurse the child. First, the baby would be offered milk in the morning when she work. Later, she might be given a chicken leg to such or weaned on food first chewed by her wetnurse to ensure that it was safe for a toothless infant to swallow.

A few years later, and 200 miles away, Elizabeth Howard woke in the maiden’s chamber at Sheriff Hutton Castle in Yorkshire, from where her father, the Earl of Surrey ruled the north on behalf of the king. She would have shared a dormitory-style room and perhaps also a bed with the other young girls of the household. Conduct manuals enjoined girls to wash their ears and brush their hair on waking, before dressing and going to greet their parents.

For noble girls such as Elizabeth, there was no early household work. After attending the chapel and then eating breakfast, they would join their mother for sewing and other ladylike pastimes. The poet, John Skelton, who later recalled a visit to Sheriff Hutton on 8 May 1495 recorded that Elizabeth and her fellow maids sewed a beautiful garland of laurel for him at the behest of the Countess of Surrey.

Elsewhere – and a generation later – Elizabeth Barton woke in the attic of Thomas Cobb’s house in Aldington in Kent. She, along with her fellow servants, dressed and went quickly about their farm tasks. Depending on the season, there was much to do, with the vast majority of Tudor teenagers entering into some kind of service in their youths – agreeing a verbal contract with a master. Elizabeth would fall ill in 1525, during her time with Cobb, soon appearing to have fits and other visions which were taken as godly.

Servants and housewives spent most of the day at work. For married women, a knowledge of cooking was seen as essential and they would spent much time preparing stews, roasted meats and other foods to feed the family.

Often they would help out in business too. Indeed, sometimes it was essential. The capable Katherine Fenkyll inherited her husband’s successfully drapery business following his death and ran it successfully for decades. She employed and oversaw apprentices, managed her goods and arranged for her ships to be loaded, all the while acquiring enough silver plate that she was feted by the prestigious Draper’s Company in London. When she joined them for their annual feasts in the 1520s it was her plate – borrowed earlier in the day – that adorned the table.

Even noblewomen were far from idle as the day progressed. Lady Margaret Hoby in the late sixteenth century, liked to pass much of the day in religious contemplation. She was also the local area’s de facto doctor and surgeon, examining and dressing the wounds of her tenants and carrying out operations. On one occasion, she attempted to save the life of a baby born without an anal passage, writing in her diary that ‘although I cut deep and searched, there was none to be found’. Women were usually expected to have a knowledge of medicine, with some, such as Cecily Baldrye of Great Yarmouth, making a professional career as a licenced surgeon in the 1560s.

Depending again on the time of year, the evenings could be long and dark. Candles were expensive, although royalty and noblewomen could afford to light their houses. Elizabeth I continued to hold evening entertainments at court until the end of her reign. As the years passed, she became increasingly conscious about the ravages of time on her beauty, smothering her face in toxic white lead and wearing elaborate wigs to hide her thinning grey hair.

Elizabeth, as the queen, could retire to a rich and curtained bed, with the curtains drawn shut against the cold. For many of her poor and elderly subjects, there was no such luxury. The aged poor of Tudor England worked until they were physically unable to do so. The lucky few were able to find a comfortable bed and food in one of the many charitable establishments that sprung up at the time. Little wonder then that so many of Norwich’s aged poor in the 1560s claimed to have been at least 100 years old: places in almshouses and charitable hospitals were highly contested.

The lives of Tudor women were so varied that any attempt to write about a day in their life is fraught with difficulty. Yet, at the heart of it, much was the same. All were born into a time in which women were less highly valued than men. A female foetus was considered only to receive a soul at 90 days gestation – forty-four days after a boy was thought to obtain his. This differential treatment would continue for the rest of their lives but, for all that, Tudor women made their mark on the world as much as men. William Shakespeare very famously set out the Seven Ages of Man in As You Like It, but a similar scheme can be advanced for women: infant, adolescent, wife or lover, motherhood, middle age, early old age and late old age. Into these broad categories slotted the life of our Tudor Everywoman.

Book Links

Amazon US (Kindle Edition)

The Book Depository (Free worldwide shipping)

I think it’s fascinating someone has decided to investigate this subject.I specifically like that it focuses on Tudor women and also that it includes not only women in the upper classes but the lesser known women as well.I’m very much looking forward to reading this.

This is really fascinating!

Will this be available for US kindle soon?