I’m excited and a little sad to share with you the final instalment of a fabulous blog post series by Brooke C. Little, about the musical education of Henry VIII and his wives. Below are links to the previous six informative articles, all of which I highly recommend you read. Happily, it’s not the last we’ll see of Brooke, as she’s joining me on Talking Tudors in December to chat about Tudor Christmas music.

Katherine of Aragon – Musica, La Granada y Canciones de Perdida de Niños

Anne Boleyn – Musical Legend and the MS 1070

Jane Seymour – Catholic Muse of English Folk Song

Anne of Cleves – Musical Ingenue; Trumpeting Queenship

Catherine Howard – “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun”

Katherine Parr – Cultivating an Aura of Musical Majesty

Henry VIII- Medieval Prince; Renaissance King

After Hans Holbein the Younger- Henry VIII, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, 16th cent.

A lesser-known image of Henry as a musician is a very small illumination taken from a psalter, or Renaissance devotional book of psalms, that belonged to Henry. Henry, in the likeness of the Old Testament’s King David, is playing the harp. Further, as no part-books or music are depicted, Henry is depicted composing the music emanating from his harp. Henry, as a musical performer is much like the Holbein representation, competent and in command of all he sets his hand to.

Pictured with Will Sommers- Royal MS. 2 A XVI, Henry VIII’s Psalter, British Library-London

King Henry VII and Queen Elizabeth of York kept a large musical retinue at court which included minstrels who played bagpipes, organs pipes, tabors, trumpets, sackbuts, fiddles, harps, recorder and horns. Placing such importance on the pleasure of listening and performance, the monarchs supported young Prince Henry in learning instrumental music by providing various musical tutors. Giles Duwes (d. 1535) also taught Henry languages, as he himself was a native French speaker, and he also became Henry’s lute teacher. Henry’s father purchased a lute for the seven-year-old prince in 1498, and according to Starkey, was largely self-taught prior to Duwes’ arrival at court. His role as primary music teacher began in 1501, prior to Prince Arthur’s death, and as Starkey puts it, the teacher assisted Henry in “polishing” Henry’s self-taught skills.

8-Course Renaissance Lute – Germany, ca. 1970;Soprano, Alto, Tenor & Bass Recorders – Germany; Cornett – Monk, 1980; Alto Crumhorn – Woods, ca. 1980

Henry also learned how to play stringed instruments and had a “school master of pipes”. In addition to employing a personal lute teacher, the court also hired a woodwind tutor called Guillam (N. D.). This private winds’ instructor may have taught him recorder and other aerophone instruments. Having received a broad musical education on a variety of instruments, Henry’s own experience may have set precedence for what was expected of the musical education of royal children. Furthermore, the gift of the lute from Henry’s father may have unconsciously persuaded King Henry VIII to gift his own daughter Mary with a lute as well. Sebastian Guistinian, the Venetian Ambassador, mentioned that as an instrumentalist, Henry played “on almost every instrument performing well on the lute and virginals.” To have had this kind of versatility as an adult, Henry likely had a broad and in-depth instrumental music experience in his young age.

The King MS 31922, also called the Henry VIII Songbook, is a collection of early sixteenth-century songs, featuring primarily secular works that circulated at Henry’s early court. What is significant about the manuscript itself is not only that it features composers that were favorites of the English court, but also that many of the secular works are attributed to Henry himself. The DIAMM places the manuscript as having been compiled between the years of 1510 and 1520 where other sources place the manuscript as having been put together in the year 1519. This ten-year time span in which the manuscript could have been copied were some of the more serene of Henry’s reign. It was a time in Henry’s life when Wolsey’s support, left Henry to pursue the pleasures he desired; hunting, jousting, dance, the games of courtly love, his other amorous pursuits, athletics, fencing and finally musical composition. Many of the texts of these pieces reflect these particular interests.

MS 31922 Binding, British Library, London

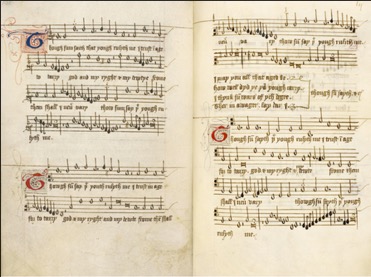

There are a variety of genres represented in the Henry VIII manuscript. Of the one hundred and nine pieces in the work the breakdown of the vocal genres are as follows; 1 motet, 1 motet-chanson, 1 English/Latin Carol, 53 English secular pieces, 12 French secular pieces, 3 French/English secular pieces, and three Dutch secular pieces. There are 35 instrumental works that scholars believe may have a connection to either French or Latin text. Henry’s 34 works receive the greatest percentage of representation in the manuscript. Shortly behind Henry’s prolificacy, are thirty-two works by anonymous composer(s). With a handful of works are, Dunstable, Busnoi, Obrect, and Isaac. The remaining works are written by Agricola, Compere, Barbirea, Cooper, Cornyshe, Daggere, Fardyng, Fayrfax, Izagha, Le Huertuer, Moulu, Sermisy, Kempe, Lloyd, Pygott and finally Rysby.

One such song is a piece accredited to Henry called “Some Say Youthe Doth Rule Me”. The lyrics may communicate Henry’s mindset between 1510 and 1520, when the manuscript was compiled. The lyrics shed light on his views on the plight of youth, religion, virtue, his marriage, and in turn where his support for women lay at the time. A selection of the lyrics of this piece is as follows;

Pastimes of youth sometime among, None can say but necessary. I hurt no man, I do no wrong, I love true where I did marry, Though some saith that youth ruleth me.

Then soon discuss that hence we must. Pray we to God and Saint Mary That all amend, and here an end, Thus saith the king, the eighth Harry, Though some saith that youth ruleth me.

These two stanzas appear at the end of the piece, accompanied by a wide leap in the voice, melodic repetition, and melismas emphasizing words like “youth”, “marry”, and “Harry”. Further, the last phrase of the line, consistent in every stanza of the work, is sung twice at the end. The original manuscript itself is written for unaccompanied solo voice; however, the last verse stands alone without written notation as if the poetry is to speak for itself without music. The melody is seemingly a quote from Henry’s popular work “Pasttime With Good Company” as it utilizes nearly identical intervallic and rhythmic components.

“Though sum saith that yough rulyth me” From the MS 31922 Henry VIII Songbook, composition accr. Henry VIII, British Library London

Though sum saith that yough rulyth me-Performed by Chandos Early Music

Sources:

Alamire, “Henry’s Music-Motets from a Royal Choirbook Songs by Henry VIII,” directed by David Skinner, recorded 2009, CD 705, Obsidian Records.

“Henry VIII Songbook, 1510-1520,” King’s MS 31922, The British Library, London, UK. f. 71.

Jane Bernstein, “Phil Van Wilder and the Netherlandish Chanson in England,” Musica Disciplina, 33 (1979): 59.

Thomas Penn, Winter King: Henry VII and the Dawn of Tudor England (London, Great Britain: Penguin Books, 2011), 183.

David Starkey, Henry—Virtuous Prince: The Prince Who Would Turn Tyrant (London: Harper Collins Publishers, 2008), 129.

John Stevens, “Carols and Court Songs of the Early Tudor Period,” Proceedings of the Royal Music Association, 77 (1950-1951): 59-60.

Weir, Allison. Henry VIII. New York: Random House, 2001.

Latest Comments