Anne Boleyn “possessed great poetic talent, and when she sang, like a second Orpheus, she would have made bears and wolves attentive. She likewise danced the English dances, skipping and jumping with infinite ease and agility. singing like a syren [and] accompanying herself on the lute …harped better than King David and handled cleverly both flute and rebec ”

Anne Boleyn is an iconic figure in history. She is famous for many things, but I am writing here about her talents as a musician and singer, and about the men and women who influenced her musical education. There are a number of contemporary descriptions of Anne, and one thing that they all agree on (even if they hated her) was her musical ability. This made her stand out in an age when it was considered normal for all well born men and women to be able to sing and play. Wolsey’s biographer, George Cavendish (who had no reason to love Anne, who he saw as responsible for his master’s downfall) says that:

“Besides all the usual branches of virtuous instruction they gave her teachers in playing on musical instruments, singing, and dancing, insomuch that when she composed her hands to play and her voice to sing, it was joined with that sweetness of countenance that three harmonies concurred.”

Although professional male musicians (at this time, there were no female professional musicians of any status) took the lead at public and religious musical events, it was usual for the daughters of noble and royal families to be given a fairly thorough musical education, as they were expected to be skilled in many social settings. They might spend a great deal of time and effort honing their musical talents, working with some of the most gifted musicians of the day. And, during their studies and at private or social occasions, they sang and played alongside other women of the court. Of course, these musical skills, along with an ability to dance, could also be seen to be an indication of their fathers’ (or once married) their husbands’ wealth and status. They would be taught instruments that would show them off to an advantage – string or keyboard instruments that could make the most of beautiful hands. Apart from the flute, it was rare for women to play wind instruments, as these were considered unsuitable.

It was the custom for the daughters of noble houses to be sent into the households of other great families from a young age – this was both for their education, and to make good political and dynastic connections. Anne was fortunate in being sent first to the court of Margaret of Austria in 1513.

Margaret at this time was the regent of the Hapsburg Netherlands – the only woman at that time to be in such a position of power. Margaret used her influence to support the arts and scholarship, filling her court with artists and musicians, including such great names as Josquin des Prez, Ockeghem, Pierre de la Rue, and Loyset Compere. She also commissioned exquisite music manuscripts both for her own use, and as gifts to family members and political allies. Anne is likely to have had lessons with the young Hapsburg girls, and to have learned music from the organist Hendrik Bredemers.

It is believed that Anne went to France some time in 1514 for the wedding of Henry’s sister Mary to the King of France, and that after Louis’ death, according to the poet Lancelot Carle she ‘was retained by Claude and became so accomplished that you would never have thought her an English, but a French woman. She learned to sing and dance, to play the lute and other instruments to drive away sorrowful thoughts.’

(Female Musicians, 1500-1550)

Anne stayed in France for seven years and during this time surely would have been influenced by her contact with a trio of powerful women: King Francis’ wife, Claude; Louise of Savoy, the mother of Francis I, and negotiator along with Margaret of Austria of the ‘Ladies Peace’; and finally Francis’ sister, the humanist and reformer, Marguerite d’Angoule?me, patron of the poet Clement Marot. Again, the French court was full of superb musicians including Claudin de Sermisy and Jean Mouton.

The painting above by the master of the half lengths shows the sort of music-making that Anne would have taken part in. As you can see, one girl plays the lute, another sings, while a third takes a part on the flute. All skills that that Anne is described as possessing.

It is one of my favourite paintings, and is relevant to Anne Boleyn in another way. If you look closely, you can actually read the music. The piece that the girls are playing is a chanson by Claudin de Sermisy with words by Clement Marot: Jouissance vous donneray (I will bring you joy).

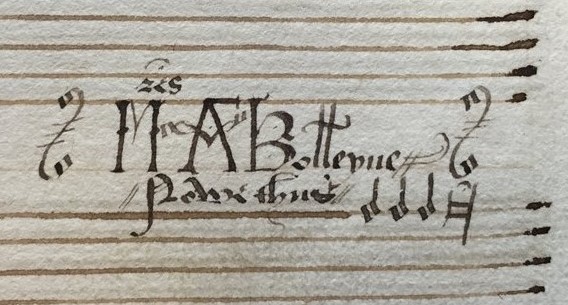

Another source of the song Jouissance is a manuscript now housed in the Royal College of Music. It is a fascinating manuscript, made up mostly of Latin sacred music by composers from the French and Flemish courts including Josquin, Mouton, and Brumel; but also containing a small number of secular French chansons including Jouissance. The manuscript itself can definitely be said to have belonged at one time to Anne Boleyn, as written between the staves below a sacred song by Loyset Compere is “Mris A. Bolleyne” along with her father’s motto, “Nowe thus”.

I could write a whole article about this manuscript alone, as many myths have built up around it, but for now, it is enough to say that it is believed that Anne brought the manuscript back to England with her when she returned from France, and that in possessing a music collection of this type, she was following the example set by Margaret of Austria.

About the Author

Latest Comments