I have long been fascinated by Holbein’s double portrait of Jean de Dinteville, French ambassador to the court of Henry VIII and George de Selve, bishop of Latour (some sources state ‘Lavaur’) but I was unaware that this very famous portrait might in fact be linked to Anne Boleyn.

Eric Ives believes that there are several reasons to suggest such a connection, with the first being the date.

‘Dinteville, on the left, arrived as the French ambassador to England shortly before 15 February 1533. The bishop came on a special visit to see Dinteville but had left by 4 June and possibly by 23 May.’ (Pg. 234)

Why are these dates significant? It was during this time that Anne Boleyn was recognised as queen and preparations for her coronation were well underway.

Holbein was also busy working on Mount Parnassus, a street tableau commissioned for Anne’s coronation.

The next reason given by Ives has to do with the reason for Selve’s visit. Rather than simply a private visit, Ives believes that he came to bring ‘confidential instructions’ to Dinteville as his ‘diplomatic instructions had been overtaken by Anne’s public recognition as queen’ (Pg. 234).

The ambassador’s original instructions were concerned with Francis I’s plan to meet Clement VII and the possibility of the pope offering ‘an accommodation over the Aragon marriage’ (Pg. 234).

This of course fell by the wayside as preparations for Anne’s coronation intensified. The ‘confidential instructions’ might also explain why the ambassador promptly abandoned his original plan and instead accepted a prominent part in Anne’s coronation.

In addition, it is also possible that George de Selve brought with him a private message for Anne.

The fact that Dinteville insisted on keeping news of Selve’s visit a secret from the duc de Montmorency (Francis I’s ‘imperialist principal minister’) further corroborates this theory.

Not convinced yet? Well there is more!

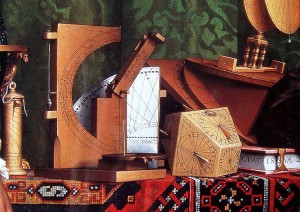

Within the painting itself there are specific references to Anne Boleyn. Next to Dinteville’s left arm there is a small wooden cylinder. This is a pillar dial and is a device used to determine dates by the sun.

(See a photo of a seventeenth century French pillar dial here.)

According to Eric Ives:

‘The settings on the instrument are clear to read and they indicate the date 11 April, in other words, the precise day on which the royal court (and no doubt Dinteville) was told that Anne was henceforward to be accorded royal honours.’ (Pg. 234)

Unfortunately, regardless of how much I cropped and zoomed I was unable to see anything very clearly on the dial. Next time I pay a visit to the full length, original portrait hanging in the National Portrait Gallery London, I will pay special attention to this instrument.

The second reference to Queen Anne Boleyn has to do with where the figures are standing. Ives explains how one would expect the men to be standing on a Turkey carpet but instead they stand on a very distinctive cosmati pavement.

But why did Holbein make this a focus of this artwork?

According to Ives, the only example of this work in England was the floor of the sanctuary in Westminster Abbey.

‘The precise spot where Anne Boleyn was anointed queen, that most solemn moment in the coronation ritual which was the distinctive spiritual mark of English monarchy, a ritual which Dinteville witnessed by special invitation of the king.’ (Pg. 235)

This is a clear reference to the high point, not only in Anne’s career, but in Dinteville’s as well.

There has been much debate over the centuries about what the instruments, including two globes, a quadrant and a torquetum actually symbolise and how to interpret these in conjunction with the religious items depicted.

There are many varying and conflicting interpretations and I suspect that people will keep trying to ‘read’ it for centuries to come but without knowing first hand the world in which it was ‘born’, I fear its true meaning will continue to elude us.

Some interesting items to note: In the top left corner of the painting, a crucifix is visible. In front of the lute is a hymnal with one page showing the Veni Creator Spiritus and on the other, the Ten Commandments.

Apart from depicting the ‘contemporary state of the Church’, Ives believes the painting also offers hope (Pg. 235). He states that,

‘Crucifix, set-square, Lutheran vernacular and texts known to all Christians together express the conviction of evangelicals that the way to unity in the Church was a response to Christ by the Holy Spirit, leading to a life of everyday obedience to the commandments.’ (Pg. 235)

A doctrine that Anne would have certainly endorsed.

My enjoyment of this complex masterpiece is now further enhanced by the knowledge that – in my eyes – it is almost certainly linked to Queen Anne Boleyn.

ReferencesIves, E. The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn, 2004.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Ambassadors_(Holbein)

Cosmati Pavement, Westminster Abbey

This is really an intriguing piece of art. And I agree, there are a lot of symbols. Since Anne was one of Holbein’s ‘patrons’ it makes sense he would find ways to honor her at her finest hour, when her influence was at its height! I’ve love to see it in person some day. I’ve been a bit under the weather, which is why I’ve been out of the loop for a couple of weeks–now on the road to recovery!

Interesting theory, but after years studying Tudor art and this painting in particular, I can’t say it I think it holds much water. A lot of the ‘clues’ like de Selve bringing a letter to Boleyn don’t have evidence behind them, and the rest is taken out of context to its original audience. Professor John North has written an excellent analysis of the religious layer interpretation, and this analysis reveals the personal layer of interpretation https://markcalderwood.wordpress.com/2014/06/13/the-ambassadors-secret/

As for the research suggestion regarding the skull in Holbein’s Ambassadors, proposing it could be Anne Boleyn’s after her beheading on May 19, 1536, Holbein and she shared very similar religious views, both advocating for a profound reform of the Catholic Church, as did Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve, the two painted characters. Could this skull anamorphosis have been added to the foreground after Anne Boleyn’s beheading as a painful memory by those who supported her cause?

See : https://www.instagram.com/ladamealalicorne.marytudor/

To write to me : jacky.lorette@laposte.net

Warmly regards from Cormery.

Jacky LORETTE