I LOOK FOR LIGHT AFTER DARKNESS:

Lady Jane Grey, England’s Nine Days Queen

by Ella March Chase

A fifteen year old girl believes her parents don’t understand her and are purposely trying to ruin her life… Sound familiar? The basic sentiment could have been my daughter’s or any one of her friends’ at that age. But Lady Jane Grey lived in Tudor England and her parents’ actions ended up costing her head. So who was Lady Jane Grey?

Images and impressions of Lady Jane Grey abound, the tragedy of her short life capturing the imagination of artists and storytellers from her time to our own. Of all the depictions, the one that touches me most deeply is that of the Romantic painter, Delacroche. Sixteen year old Jane faces death for High Treason. Her crime: Being forced by her ambitious parents to wear a crown she never wanted. She kneels, garbed in a martyr’s flowing white gown. A blindfold blots out the last light she will ever see. While details of the painting aren’t accurate, the emotional impact of Jane’s death is well portrayed—an innocent girl is about to die for the crimes of parents who were supposed to protect her.

Even Henry VIII’s eldest daughter Mary, the queen Jane so briefly deposed, knew that Jane had tried to resist the plot her parents and the ruthless John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland spun with her at its center. As princess, Mary had been victim in her own father’s campaign to annul his marriage to her mother, Katherine of Aragon, fostering in her an understanding of exactly how her young cousin had been maneuvered into committing treason.

So how did Jane begin her journey to Tower Green? The Tudor era was harsh to its daughters. Educating them at all was still considered an experiment, and there was scholarly debate as to whether or not women even had souls. One of the premier educators of the age, Juan de Vives, condemned any outward show of maternal affection, saying that ‘if tenderness destroys sons it utterly ruins daughters’. It was a sentiment Jane Grey’s parents took to heart.

They were an ambitious pair, courtiers whose ancestors had gambled and won more power than their humbler origins could have predicted. Henry Grey was descended from the first marriage of Elizabeth Woodville, who later ‘bewitched’ Edward IV into making her queen. Frances Brandon Grey’s father was Henry VIII’s best friend. When the king’s famously beautiful sister lost her elderly first husband, the French king François II, Brandon was sent to fetch her back to England. The pair eloped in a marriage people called ‘cloth of gold and cloth of frieze’.

Like their forbears, Henry and Francis Grey were notorious gamblers. From the moment Jane was born they assuaged their disappointment that she was not a son by instituting a draconian regimen designed to make her a suitable queen for Henry VIII’s son. Every move Jane made was criticized, every task a test of skill and grace. The pressure must have been unbearable for Jane. Most parents would have delighted in the solemn, sensitive child’s many gifts.

Jane’s scholarship surpassed even the remarkable intellects of her royal Tudor cousins Mary, Edward and Elizabeth. (A fact vain Princess Elizabeth probably never forgave her for.) Jane was happiest when she was with her tutor, John Aylmer. She wept when lessons were over and she had to return to her parents.

In his book, The Schoolmaster, Elizabeth Tudor’s beloved tutor, Roger Ascham, recounts his first meeting with Lady Jane. He arrived at Bradgate Manor to find her parents out hunting and Jane immersed reading Plato in Greek. Jane told him that when she was in the presence of her parents she must do things ‘so perfectly as God made the world or else I am so sharply taunted, so cruelly threatened… sometimes with pinches, nips and bobs and other ways which I will not name for the honor I bear them… that I think myself in hell.’

But in 1547, when Jane was nine years old, she tasted a far happier life, finding a mother figure who gave her the tenderness and approval she craved. As was the custom, Jane was sent to serve as a maid of honor to a highborn lady, where she was to learn the ways of court. Her mistress– the recently widowed Lady Katherine Parr—had been Henry VIII’s sixth queen. Jane had scarcely arrived at the Dowager Queen’s palace at Chelsea when Parr remarried. Her new husband was Lord Admiral Thomas Seymour, Jane Seymour’s brother and uncle to the new king Edward VI. An adventurer with his eye on the main chance, Seymour did not shrink from using women and children to advance his ambition.

In the beginning, the couple was happy and Jane’s affection-starved life was transformed as Parr swept her into a circle of the most intelligent women in England– women devoted, not only to the classical education that comprised The New Learning, but to the reformed religion. Parr had even written books, an accomplishment Jane greatly admired. Jane went from being criticized, pinched and slapped to being praised, petted and adored. The eager-to-please child blossomed, but her idyll was not to last. Katherine Parr had another ward of royal blood—Princess Elizabeth, daughter of Anne Boleyn. When the now-pregnant Parr discovered her husband attempting to seduce the princess, she sent Elizabeth away. But the betrayal was something Parr never recovered from. She suffered complications from childbirth in September 1548. After days of delirium, she died with Jane at her side. Eleven year old Lady Jane served as chief mourner, the little girl dressed in black, walking at the head of the funeral procession. Parr’s fever-spawned ravings that Seymour had poisoned her so he could marry Princess Elizabeth doubtless haunted Jane the rest of her life.

Jane was returned to parents who did not understand her, but the brow-beaten child had tasted motherly affection. She was also growing up. In the years that followed, she began to show disdain for her parents’ runaway ambition.

When it became clear the fifteen year old King Edward was not going to survive tuberculosis long enough to marry, Jane’s parents and the powerful Lord Protector, John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland faced a dangerous dilemma. When Edward died, Catholic Princess Mary would ascend to the throne, taking power from the protestant faction that had been her enemy. Frances Grey had been a childhood playfellow of Princess Mary, and still lavished her cousin with protestations of her affection, even while embroiled in a plan to seize the throne, make Jane a puppet and—with Northumberland—rule England.

The first stage of the plot hinged on cementing a marriage between Jane, with her Tudor blood, and Dudley’s youngest son, Guilford. Jane—smart girl that she was—feared and hated the Duke of Northumberland, as did most of England. When her parents insisted she marry Northumberland’s son, she defied them. Her mother beat her until she surrendered.

While the wedding was held with royal pomp, the gravity of the king’s condition was kept secret, especially from his sisters. As soon as the festivities were over, Northumberland raced back to the king, threatening the dying boy with hellfire. Surely, Northumberland insisted, that was what would await a king who allowed a catholic to inherit his throne, condemning his subjects to the evils of Catholicism. Few people but Northumberland and the Greys knew the extent of the horror inflicted on the helpless boy—a crone Northumberland hired to nurse Edward was dosing the king with arsenic, keeping him alive but in agony until Edward finally signed the new Act of Succession, naming Jane as his heir.

During Edward’s ordeal, Jane was suffering as well, her hair falling out and her skin and fingernails peeling. She was so terrified of Northumberland she believed he was poisoning her. She still didn’t realize Northumberland’s goal was the throne and that his plot hinged on her being alive.

There is a lovely romantic legend that Jane and Guilford Dudley fell in love—a story that has been perpetuated in books and movies. But the two were ill suited to each other, Jane’s hatred and fear of the Dudleys growing fiercer when she realized the purpose behind the forced marriage.

With the king’s order of succession signed and the privy council coerced into accepting Jane as queen, Northumberland sent a message to the princesses Mary and Elizabeth to rush to their brother’s death bed to say farewell. The king was already dead, though only a trusted few knew it. Canny Elizabeth suspected foul play and claimed to be too sick to travel. Mary, however rushed toward London, a party of armed men under Robert Dudley, who would one day become Queen Elizabeth’s great love, the Earl of Leicester, set out to capture her. There was no question in any of the conspirators’ minds both Mary and Elizabeth would have to die.

Meanwhile Jane, who had been taken to Chelsea to recover from her illness in a place of happy memories, was summoned to Syon House. Still oblivious to her parents’ plans, she was stunned to be greeted as ‘our sovereign lady’. When Northumberland led the poor girl toward the empty throne, his intent became clear. She must have been terrified. She had seen enough of the bloody Tudor court to know the consequences that would await her if the coup failed.

She resisted Northumberland and her parents, saying: “The crown is not my right and pleaseth me not. The Lady Mary is the rightful heir.” When they pressed her further, Jane fainted onto the stone floor. No one came to her aid. She lay there an hour, alone, terrified, awoke weeping and began to pray aloud, begging God to give her a sign as to what she should do. Even God, it seemed, wasn’t listening. In the end, she reasoned the decision out herself, deciding that if she could keep the country protestant, that was her duty. She mounted the throne, knowing there could be no turning back. When the Archbishop tried the crown on her head, he said they would need to make another for her husband. Shy, solemn, obedient Jane—the girl who was to be queen in name only—stunned her parents and Northumberland by refusing Guilford the crown. If God saw fit to make her queen, then she would be queen. She would make Guilford a duke.

Northumberland and Jane’s parents were furious at her disobedience, but they could not beat a queen into submission. But Jane’s was not the only rebellion among those privy to the plot. Someone had sent a messenger to warn Princess Mary en route. The news must have been crushing when it came: Robert Dudley had failed to take the princess prisoner and Mary had declared herself queen. People flocked to Queen Mary’s banner. Most Englishmen hated the greedy Northumberland, and only knew Jane as the wife of a Dudley. Mary, however, was the peoples’ beloved princess. They had loved Catherine of Aragon, loved their kind Princess Mary. They had seen her suffer under Anne Boleyn and King Henry who had declared Mary a bastard forced to be a servant in the household of the half-sister who had displaced her. Now, they were willing to fight to put right that injustice.

An ominous quiet fell over London as Jane was proclaimed Queen throughout the city and made the traditional trip by royal barge to the Tower of London to await her coronation. She would never leave the fortress a free woman.

Perhaps the most poignant words Jane spoke came in the Tower rooms where she held court as queen for such a brief time. Northumberland’s forces in the north had been crushed by Queen Mary’s troops, the nobles left to defend Jane had deserted, all of them proclaiming for Queen Mary, trying to save their own skins. Mary’s army was nearing London. Jane’s father rushed in and tore the cloth of estate from over her head, saying “Long live Queen Mary”. In the midst of the chaos and defeat, sixteen year old Jane asked her father: “Can I go home now?”

No. Henry and Frances Grey joined the flood of people deserting Jane. Imagine Jane at the window, watching them leave her to face Mary’s angry troops and the rightful Queen by herself.

In the months that followed, Frances Grey would restore her family’s fortunes, flinging herself on her tenderhearted cousin’s mercy, begging for her husband’s life. The new Queen pardoned Henry Grey, restored his lands and title. The Queen even made Jane’s younger sisters Lady Katherine and Lady Mary maids of honor. During her appeal to the Queen, Frances Grey never mentioned Jane.

Jane was convicted of high treason in November of 1553. The sentence: to be burned alive or beheaded at the Queen’s pleasure. Many of the nobles who condemned Jane had plotted with her father. In spite of the verdict, Queen Mary intended to pardon Jane once Mary had wed and produced a royal heir to the throne.

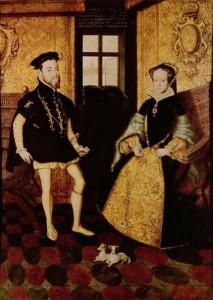

But the reign that had begun in an outpouring of love and loyalty to the embattled catholic princess crumbled under the pressure of the ongoing religious conflict. As Mary began to return Protestant England to the Catholic fold, even Northumberland recanted his faith and became Catholic in hopes of being pardoned by her. Jane, still imprisoned in the Tower, waged her own battle, corresponding with the most powerful Reformers in Zurich and Geneva. When Queen Mary betrothed herself to the Spanish Prince Philip, her subjects began to fear England would be swallowed up by the powerful Hapsburgs and the Inquisition would light the fires of Smithfield once again.

When Thomas Wyatt of Kent and some other nobles mounted a rebellion to rid the country of the Spanish threat the protestant faction hoped to put Princess Elizabeth on the throne. Unfortunately Henry Grey took up arms and made the fatal cry “For Queen Jane”, sealing his daughter’s fate. Wyatt reached Southwark, and Jane could hear the cannon fire from her prison, though she didn’t know what was happening. When it was over, the rebellion crushed, Prince Philip’s father refused to let Mary’s bridegroom sail to England until Jane Grey was dead.

In a desperate attempt to save Jane’s life, Queen Mary sent Father Feckenham, her own confessor to the Tower, to convince Jane to convert. Mary’s hope—that the conversion would neutralize the threat so that the Spanish would allow Jane to live.

Though Jane came to admire the kind Feckenham, she held firm in her faith, hoping ‘for light after darkness’. When it became obvious to all Jane would not be moved, Jane asked Feckenham if he would do what neither of her parents had ever done— stay with her to the end. Feckenham, who had come to hold Jane in great affection as well, promised he would.

The morning of her execution, Jane watched Guilford Dudley make his way to Tower Hill, saw his bloody, headless body on its return in a cart. He had been as much a pawn as she was. When Jane made that terrible journey to the block for her parents’ ambition, Feckenham was at her side. Jane, so determined to die with the dignity befitting a princess of the blood, still had a moment of terror as she saw the headsman. “I pray you dispatch me quickly. Will you take it off before I lay me down?” she asked her executioner. “No madam,” he said. She picked up the blindfold, tied it on. In the Delaroche painting that captures her last moments her executioner grips the axe he’ll use to sever her head. Her grieving ladies in waiting crumple to the floor and solemn faced men avert their eyes from the injustice about to take place. She is trying so hard to die with dignity. You can almost hear her heartbreaking plea to the headsman. “Will you take it (my head) off before I lay me down?” She gropes for the block, unable to find it. “Where is it? What shall I do?”

Artist Delaroche paints Feckenham reaching out to Jane, guiding her toward the inevitable.

I hope the last thing Jane Grey felt was the touch of a kind friend. She was just sixteen.

Visit Ella March Chase’s official website here.

Great article. Can’t wait to read the book.

Such a tragic story…

This de me want to cry! She was my age! Her parents were deplorable.