Until the fifteenth century, people exercised in order to be ready for war (Thurley, Pg. 179).

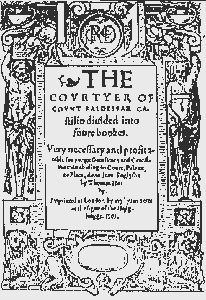

In the fifteenth-century in Italy there was a revival of interest in physical fitness and in 1527, Castiglione in his Book of the Courtier (1527) was one of the first to highlight some other benefits of exercise.

“Turning away from the medieval idea of ‘sport’ for war’s sake, he advocated it in terms of social benefit, to be played in a gentlemanly manner as one of the accomplishments of a courtier.” (Thurley, Pg. 179)

In 1531, Sir Thomas Elyot in The Boke Named the Governour recommended sport because ‘by exercise, whiche is vehement motion…the helthe of a man in preserved and his strength increased.’ (Thurley, Pg. 180)

He spoke about the importance of exercise in maintaining not only physical strength but mental health as well. Sir Thomas recommended exercise because it improved digestion and made ‘the spirits of a man more strong and valiant’ (Sim, Pg. 184).

In 1527, Castiglione stated that tennis was a ‘noble sport which is very suitable for the courtier to play…for this shows how well he is built physically, how quick and agile he is in every member.’ (Thurley, Pg. 182)

By the sixteenth century tennis was already an old game. The exact origins are disputed but it was certainly being played from the twelfth century onwards in France and Spain.

The name ‘tennis’ probably came from the French custom of calling out ‘tenez’ before serving (HCP Factsheet).

Interestingly, Simon Thurley points out that ‘two French kings, Louis X and Charles VIII, and two Spanish kings, Henry I of Castile and Philip the Handsome, all died as a direct result of their participation.’ (Pg. 185)

The game was also taken up in England but was banned in royal ordinances between 1305 and 1388. According to Thurley, it was played at court in the reign of Henry V and then again under Edward IV (Pg. 185).

In this view of Windsor Castle, the tennis court can be seen in the ditch around the round tower. Hollar, 1672.

It was not until the reign of Henry VII that tennis became popular at the English court. The king took the game up and as a result of his interest made a tennis-play at Kenilworth, and, in the next fifteen years, went on to construct courts at Richmond, Wycombe, Woodstock, Windsor and Westminster (Thurley, Pg. 185).

Tennis was a spectator sport, which meant a great opportunity to show off your skills and to gamble! Both players and spectators could bet on the outcome, with the privy expenses showing that even the King could get it wrong. Between 1493 and 1499, Henry VII lost a total of £20 (Thurley, Pg. 186).

It was a different game to our modern tennis. In the sixteenth century, there were two versions of the game played on differing courts.

Simon Thurley describes the differences in ‘The Royal Palaces of Tudor England’:

The first version was the quarre court (or what Scaino called the minor court) which took its name from a small hole, one foot square, in one wall. This was the older form of the game which eventually died out at the end of the seventeenth century. The court had penthouses on the long wall and on the side opposite the service end (the hazard side), it also had a ‘grille’ which was a netted opening above the penthouse. This sort of court was the smaller of the two…The other form of court was called the dedans or major court. It took its name from the dedans – a third penthouse replacing the quarre at the service end of the court. (Pg. 185)

To play the game you served the ball on to the penthouse and then returned it across the net, or cord that was frequently used in place of a net (Sim, Pg. 185). 18 feet up the wall there was a ‘play line’, with balls not permitted to hit above this line, although players could hit the ceiling (Thurley, Pg. 185).

Points were determined by how far from the net and unreturned ball came to rest (the chase). If you were playing the quarre court you could also score points by hitting the grille or quarre. Hitting the dedans also scored you points (Thurley, Pg. 185).

Tennis formed part of a young Henry VIII’s education alongside hunting and archery.

One of the first building projects of his reign was a new ‘tenys playe’ at Westminster (Thurley, Pg. 186). Over the next 20-25 years he went on to double the number of courts he owned by building tennis-plays at Beaulieu, Bridewell, St James’s, Greewich, Calais, Whitehall and Hampton Court.

The most impressive of Henry’s courts were ‘the great covered courts’ built at Hampton Court Palace and Whitehall in 1532-33.

Henry was not alone in his enjoyment of tennis, as many courtiers played including, ‘Lords Rochford and Ros, the Dukes of Suffolk and Buckingham, Henry Courtenay, Earl of Devon, and Anthony Knyvet.’ (Thurley, Pg. 188)

Interestingly, it looks as though courtiers had to pay to use the courts. At Richmond, in 1519, 2s. 6d. per day was the going rate!

On the day of Anne Boleyn’s arrest, she spent part of the morning watching a game of tennis at Whitehall. According to Alison Weir,

‘Her champion won, and she was regretting not having placed a bet on him when a gentleman messenger came’ and asked her to present herself before the Privy Council (Pg. 132).

Real tennis is still played today in the United Kingdom, United States, Australia and France. There are fewer than 50 real tennis courts left around the world and only a few in which the public can watch a match.

One of these courts is at Hampton Court Palace where you can see a Royal Tennis Court building that dates to 1626, probably built on the site of an earlier court.

The court is home to a club of over 500 members and according to the official website of The Royal Tennis Court, ‘has been in more or less continuous use since it was built’.

The terms ‘Royal’ and ‘Real’ were only introduced in the mid twentieth century to distinguish this ancient form of tennis from lawn tennis that developed in the late nineteenth century.

(Click here to see an illustration of a game of tennis being played in the reign of King Henry VII)

Learn more about real tennis in this short video.

Fast Tube by Casper

Sim, A. Pleasures and Pastimes in Tudor England, 2009.

Thurley, S. The Royal Palaces of Tudor England, 1993.

Weir, A. The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn, 2009.

Wikipedia Article on Real Tennis

Real Tennis and The Royal Tennis Court at Hampton Court Palace

The Royal Tennis Court

I actually played real (royal) tennis–well, I knocked a ball around a royal tennis court–but never in aristocratic company. The lists seem to miss the court at my former school, Canford, in Dorset. See http://www.canford.com/ > “Search” for “royal tennis”. You get this notation: “Canford School boasts one of the few Real (Royal) tennis courts in England. The court dates back to 1879, when it was built by Sir Ivor Bertie Guest, then Lord Wimborne.The game of Real Tennis itself goes back to the days when the monks played in their mo…” Whatever came next seems to have gone.

Thanks for sharing this information Robert. I might have to give it a go one day, although I fear that I would be terrible!

It looks an interesting and physically challenging game and one worth preserving as one preserves old words and expressions in modern parlance. More power to it.

Elements of esku huskako pilota, the barehanded version, and of the Trinquet still in use today in Pelota (see St Jean de Luz) are evident in the Real Tennis game of today.