1553-1554

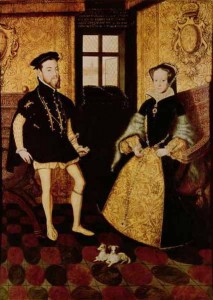

In July 1554 an Armada sailed from Corunna. Unlike the later Armadas from Spain, this was a peaceful flotilla, carrying a Spanish groom to his English bride.

Bound by a promise to his father – the reluctant groom was bound to try to impress. Bound by oath (betrothed) the Infante was bound by honour. Both bride and groom were bound by treaty to unite Tudor and Hapsburg dynasties. Both were also bound upon an enterprise that would reunite England with See of Rome. All in all this Spanish Armada was bound to make history.

The flagship was resplendent in scarlet and crimson and gold. The Espiritu Santo, a galley of twenty four oars, like the groom himself, was decked-out in all its finery. The fleet carried a retinue of grandees and nobles of Castile and Aragon. The decks were crowded with gentlemen of Infante Felipe’s privy chamber and retainers of this royal household. Hundreds of carved chests were filled to busting with a wardrobe of a scale that Henry VIII or Francois I in their pomp might have blushed to own. The Infante in his younger years wasn’t the dull blade he was later painted in his old age.

Most importantly the fleet of one hundred and twenty five ships carried three million ducats in gold. Prayers for safe-crossing must have been particularly fervent on the English side.

Infante Felipe boarded his flagship prince; he disembarked king. This was a return of favours between father and son. Philip had offered his hand to Queen Mary as a filial duty. Emperor n Charles V repaid his son’s obedience to the dynasty by making Infante Felipe king in his own right – twice over: king both of Naples and Sicily; and also of Jerusalem. The Holy Roman Emperor might be short of much, including men and money from time to time, but kingdoms he possessed in superfluity.

Upon his father’s abdication late in 1555, the Infante and his bride were destined to add to these kingdoms, those of Spain and its Empire. In consequence Infante Felipe is known to history as Philip II of Spain.

By 1556 Philip II and Mary I together ruled the remnant Burgundian lands ( Belgium, Luxembourg and Netherlands and parts of Alsace-Lorraine); the principal kingdoms of Spain; her Empire in the Americas; Naples, Sicily, and a string of Mediterranean possessions including Cyprus and Malta; the duchy of Milan; as well as England and Ireland. Both regnant, both were styled archdukes of Austria and of counts of Brabant…they also used of the style of King and Queen of France. And Philip II commissioned in 1556 a series of windows to honour his marriage; his wife and their dynastic alliance permanently in stained glass – that at Gouda being the most famous.

This is England as an Empire a century before its Imperial day dawns in the late seventeenth century. The male heirs of this marriage were to inherit these Hapsburg lands. The male heirs of this marriage were also to be educated in and were to live in England – at least until their majority. England immediately enjoyed the commercial and economic privileges of belonging to the territorial archipelago of the Hapsburg dynasty whilst entirely retaining its self-governing autonomy. English nobles were given Spanish pensions in gold. Rarely has one marriage achieved so much. Equally rarely has one marriage subsequently received such poor reviews from History.

That must beg the question, why?

To fully answer that question it must be understood that Queen Mary I’s reign lies awkwardly across two separate if contiguous fault-lines.

The first lies buried in the spoil of the confessional earthquakes of Reformation and Counter-Reformation. Evocations of a chosen people’s divinely ordained Manifest Destiny were rooted in the doctrines of the radical evangelical Reformation theology that piecemeal came to dominate the English church. Consequently, it also shaped English nation’s political consciousness.

The second lies within the pages penned by the pioneering historians of the nineteenth century. Misunderstanding chronological order for scientific method and misapplying scientific evolutionary theory, the emergent pseudo-Darwinian narrative was polluted by an odd mixture of linear determinism and jingoistic hagiography. Sadly this unhistorical poison still freely runs through the Tudor history taught in our schools. Menacingly, it continues to obscure the historical realities of Queen Mary I and of her reign.

Therefore, in order to see the events of 1553-4 as they really were it is first necessary to set aside prejudices embedded in our collective psyche and based upon these antique misunderstandings.

Problems come in quick succession

Mary I’s accession was a coup d’état in response to a coup d’état. It was entirely unpredicted. Its completeness concussed the political elite in the Privy Council. Its speed overwhelmed London and the wider political nation.

Reeling, the rudderless elite were left leaderless. Before they could regroup it was over.

In August 1553 Queen Mary was securely established in the Tower: in power; in place. In many areas of business there was no doubt what her accession meant. In the previous six and a half years she had personified the opposition to the increasingly radical Reformation that had swept aside the Mass; the sacraments; the priestly caste; and legal clerical estate.

The traitorous John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland and Vice-chamberlain Sir John Gates made very public reconversions to the old faith. They received the Eucharist in public at Mass before their executions. Their actions were more than token gestures: they recognised a new governing reality.

But there were other aspects to her accession which were wholly without precedent. And no one could certainly know their effect since Mary I was England’s first queen regnant.

From little things – the queen occupied the king’s side of the royal palaces – greater things inevitably flowed.

Palaces were designed to accommodate the dynamic of male access and egress to and from rooms. In this man’s world the royal peacock might strut at will from room to room and place to place trailed by his fantail of gentlemen.

A queen’s could not: modesty proscribed and etiquette prescribed her movements in court. Direct access to men – even to male body servants – was restricted. Pages, sewers and grooms and other male body servants were placed firmly on the far side of the chamber doors to the person of the queen…when she was alone.

Privy Councillors, ambassadors and such could no longer follow the queen into the anonymous intimacy of the royal apartments. The privy chamber and closets and bedchamber were generally out of bounds, save to the queen’s gentlewomen. Discussions that previously tended to occur in the privy chambers were now intended to take place more publically in the council chamber and its galleried environs. Policy debates took place within earshot of the great chamber.

The novelty created an unfavourable impression of destabilising tumults of discussion. This only served to reinforce male prejudices. And then as now impressions can be defining even when they’re based upon misunderstanding.

It is essential to understand female accession precipitated a new physical and practical reality within a both the physical and the conceptual space where government occurred. The change required many accommodations of form and practice; inevitably, these bumped up against established habits; many male egos are bruised; in consequence there was bound to be a lot of grumbling – from both sides.

Although state papers, chronicles and ambassadorial calendars all pick-up this background noise historians should not mistake this for weak, chaotic decision-making….

To be continued…

I always felt so sorry for everyone involved. Phillip, Mary, Elizabeth. An unhappy trio. to be sure.

Such a whirlwind of change and confusion at this time, and such turmoil and sadness as well….