How to eat to save your life (and soul) by Vanora Bennett

By chance, I started a diet on the first day of Lent. I marked the night before, Shrove Tuesday, by making maximum-calorie pancakes for my children and thought no more about the coincidence. But, as the pounds slipped away in the forty days that followed, that awareness of Lent came back to me. I found myself reading more and more about the religious fasts, and feasts, of the Middle Ages (I am a historical novelist, after all) and realizing that our pre-modern ancestors lived by an extraordinary and complex system of culinary balance that was designed and able to promote perfect health.

Europeans from 1200 to 1500, the pre-Reformation period when Western Christianity was at its most cohesive, lived by a religious – and culinary – calendar of alternate feasts and fasts. Both fasting and feasting were gestures of faith in God and trust that the divinely ordered world would provide for mankind at the right time. In an age when churchgoing could be sporadic, it was the act of fasting for between half and a third of the days of the year – on Wednesdays, Fridays, sometimes Saturdays, for the Advent month before Christmas, and the entire Lenten 40-day period before Easter, as well as at the beginning of every quarter and before the most important saints’ days – that really defined Christians as a g roup.

Europeans from 1200 to 1500, the pre-Reformation period when Western Christianity was at its most cohesive, lived by a religious – and culinary – calendar of alternate feasts and fasts. Both fasting and feasting were gestures of faith in God and trust that the divinely ordered world would provide for mankind at the right time. In an age when churchgoing could be sporadic, it was the act of fasting for between half and a third of the days of the year – on Wednesdays, Fridays, sometimes Saturdays, for the Advent month before Christmas, and the entire Lenten 40-day period before Easter, as well as at the beginning of every quarter and before the most important saints’ days – that really defined Christians as a g roup.

Fasting didn’t mean starving, except for the wilder type of early Christian ascetics, woolly-bearded mystics living on dried grasses and locusts, or anorexic girl nuns with their heads full of visions of their bridegroom, Christ. It’s true that a few radical Christians, among them St Catherine of Siena and St Francis, all but starved themselves to death in pursuit of an extreme ideal of extinguishing sinful impulses not only of gluttony but also the more dangerous sin of carnal desire.

Fasting didn’t mean starving, except for the wilder type of early Christian ascetics, woolly-bearded mystics living on dried grasses and locusts, or anorexic girl nuns with their heads full of visions of their bridegroom, Christ. It’s true that a few radical Christians, among them St Catherine of Siena and St Francis, all but starved themselves to death in pursuit of an extreme ideal of extinguishing sinful impulses not only of gluttony but also the more dangerous sin of carnal desire.

But for the overwhelming majority, and for the Church itself, fast days were low-key affairs. Very practical considerations governed Church leaders as they established the calendar of fasting in the early centuries of Christianity. The Church went more easily on the faithful in the summer, when maximum strength was needed for bringing in the crops, or making food for winter, and when hot weather and long days meant people had to be on their feet for more hours. The two big blocks of fasting time – Advent in December and Lent in March – both occurred in the low season for food production, when days were short, work minimal and food running low.

But for the overwhelming majority, and for the Church itself, fast days were low-key affairs. Very practical considerations governed Church leaders as they established the calendar of fasting in the early centuries of Christianity. The Church went more easily on the faithful in the summer, when maximum strength was needed for bringing in the crops, or making food for winter, and when hot weather and long days meant people had to be on their feet for more hours. The two big blocks of fasting time – Advent in December and Lent in March – both occurred in the low season for food production, when days were short, work minimal and food running low.

For most believers, fast days meant making two relatively undramatic changes to their lives: first, missing out the meat and animal fats that stimulated the body most of all foods from the daily diet, and replacing it with fish or other proteins and olive oil rather than animal-based butter or lard, and, second, skipping one meal, and moving the midday main meal to a few hours later in the day.

Practitioners loved the sense of lightness and well-being that these few hours of regular abstinence – a whole-body prayer – brought them. Adalbert de Vogué, a monk of the Abbey of La Pierre-qui-Vire in France, and author of To Love Fasting: A Monastic Experience, wrote of the time in the afternoon when it was coming up to 24 hours since he’d last eaten: “My mind is at its most lucid, my body vigorous and well disposed, my heart light and full of joy.”

Practitioners loved the sense of lightness and well-being that these few hours of regular abstinence – a whole-body prayer – brought them. Adalbert de Vogué, a monk of the Abbey of La Pierre-qui-Vire in France, and author of To Love Fasting: A Monastic Experience, wrote of the time in the afternoon when it was coming up to 24 hours since he’d last eaten: “My mind is at its most lucid, my body vigorous and well disposed, my heart light and full of joy.”

To the medieval mind, this pattern of balancing periods of heavier and lighter eating, based on the time of the year – using food to promote virtue – was only part of a broader belief system that seeking perfect balance was at the centre of being, and that balance in the diet would help promote not just health but peace of mind that all was in harmony in the world.

Medieval man based his entire life on this belief, and it certainly governed everything that went into his stomach, during both feasts and fasts. Medicine and cooking both reflected the teachings of Galen (or Galienus), the second-century Greek physician, that the entire universe was a combination of the four elements – fire, air, water and earth – and that each living being’s nature was determined by a unique combination of the four factors, hot, cold, dry and moist, that were expressions of those four elements. Medieval thinking had it that a man could call himself healthy when the various elements of his body combined in a stable and balanced manner. If one of the four “humours” dominated, whether because of a temporary state of illness (fever, for instance, made you hotter than usual), or because of old age (which was deemed to make you colder and drier than the young, who were prone to being too hot and moist), it was important to restore the balance.

One way to do that was by changing what you ate – a notion that will be familiar to anyone interested in Indian Ayurvedic practices today. Medieval dietetics sought to match the individual with foods with optimum characteristics to achieve a temperate, balanced state – warm and moist.

One way to do that was by changing what you ate – a notion that will be familiar to anyone interested in Indian Ayurvedic practices today. Medieval dietetics sought to match the individual with foods with optimum characteristics to achieve a temperate, balanced state – warm and moist.

If you had an illness that made you too moist, you were supposed to eat more food classified as “dry” – beef, for example, or game birds. If you were “dry” yourself, you should, by contrast, eat more “moist” food – young meat, such as suckling pig or lamb. And if you had good health, you should stick to a balanced diet of temperate foods.

I was charmed by the idea that – unlike modern eaters, who are so suspicious of their relationship with food, watching themselves for food fetishes, addictions, obsessions and allergies – medievals were so positive about what they ate, believing they could treat their own illnesses by altering the food they consumed. I was still more charmed to find out that medieval doctors, like the self-indulgent in modern life, also held that “a little of what you fancy does you good”, and that you would benefit medically from eating the dishes you like best. Or, as the physician Magninus of Milan put it in his health and cooking manual, Opusculum de Saporibus (A Treatise on Tastes): “What is more delectable is better for digestion.”

I was charmed by the idea that – unlike modern eaters, who are so suspicious of their relationship with food, watching themselves for food fetishes, addictions, obsessions and allergies – medievals were so positive about what they ate, believing they could treat their own illnesses by altering the food they consumed. I was still more charmed to find out that medieval doctors, like the self-indulgent in modern life, also held that “a little of what you fancy does you good”, and that you would benefit medically from eating the dishes you like best. Or, as the physician Magninus of Milan put it in his health and cooking manual, Opusculum de Saporibus (A Treatise on Tastes): “What is more delectable is better for digestion.”

Cuisine combined and manipulated this process of eating for health and happiness, according to Massimo Montanari, author of Food is Culture.

Cooking food altered its balance by adding heat and either moisture (if boiling) or dryness (if roasting); any imbalance created by this was in turn counterbalanced by the addition of herbs and spices, to add heat and dryness, or fruit, wine, or vinegar, to add cold and moisture, to create a meal that was both tasty and nutritional.

“For the people of the Middle Ages, cuisine was an artifice,” Montanari wrote in Food Is Culture. “Renaissance and medieval taste had a model of cuisine that flavours should be blended for optimal health. Balance was all-important.”

“For the people of the Middle Ages, cuisine was an artifice,” Montanari wrote in Food Is Culture. “Renaissance and medieval taste had a model of cuisine that flavours should be blended for optimal health. Balance was all-important.”

These culinary balancing acts could draw the badness out of even the most extreme and perilous foods. Seasoning and combining foods could correct any “vice”. Fruits, judged so excessively cold and moist by most cooks and doctors that they were thought dangerous for the health, could be made safe by being “warmed” – in the case of melon, with a slice of salted pork (melon and prosciutto are still a popular pairing in modern Italy) or by sprinkling the fruit with drying, heating salt (as it is still sometimes eaten today in France). Pears, almost as noxious as melon if eaten alone, became healthy if poached with aged red wine and “warming” spices, such as cinnamon, cloves and sugar, another combination that survives to this day.

But, most important of all for both cook and physician, was the balancing of dishes with appropriately complementary sauces – a cold, moist fish, say, balanced by a hot, dry sauce. As Montanari explains, “the Galienus cook took care with sauces to temper the dish and make it digestible and tasty at the same time.”

The spices imported from the East and used in cooking for the elite each had medicinal as well as taste properties.

The spices imported from the East and used in cooking for the elite each had medicinal as well as taste properties.

Cinnamon fortified the liver and stomach; cloves eliminated flatulence and evil humours due to cold. Medievals, who even more compulsive classifiers than the Victorians, wouldn’t have been medievals without turning the business of matching foods into an elaborate game of numbers.

Magninus’s book deals systematically with the major meats, fowl and fish, summarizing each one’s physical characteristics, then explaining the best way to cook and sauce it. The dryness of beef meant not only that it should be boiled but also that it should be served with a hot sauce to warm and tenderize it. He recommended saffron pepper sauce, or rocket, or white garlic. Goose’s crude, cold and moist nature lent it to a sauce of roasted bread and bouillon, strained with six cloves of crushed garlic and mixed with ginger, all boiled together in a pan. Hot, dry salt was a good seasoner for crude moist pork. But it wasn’t needed for dry foods and delicate fowl such as chicken. Legumes, on the other hand, needed not just salt and water but in butter, oil or fat as well. Because they were by nature melancholy and earthy, a fatty seasoning would make them smoother, more delectable and therefore more nourishing.

The degree of heat each spice or condiment brought to a dish was carefully classified, too: pepper was considered of the fourth degree of hotness and dryness, while cloves and cardamom were of the third degree, and milder cinnamon, cumin and nutmeg only of the second degree. Native flavourings were likewise classified: the fourth degree included garlic, mustard and pepper, the third degree parsley, sage, leeks, and garden watercress, and the second degree fennel, caraway seeds, chervil, mint and rocket.

The degree of heat each spice or condiment brought to a dish was carefully classified, too: pepper was considered of the fourth degree of hotness and dryness, while cloves and cardamom were of the third degree, and milder cinnamon, cumin and nutmeg only of the second degree. Native flavourings were likewise classified: the fourth degree included garlic, mustard and pepper, the third degree parsley, sage, leeks, and garden watercress, and the second degree fennel, caraway seeds, chervil, mint and rocket.

Cuisine was fairly uniform across Europe in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance (though southern countries tended to use more olive oil, citrus fruits, and Middle Eastern vegetables such as aubergines, while northern countries favoured more butter, ale, peas and beans, and English cooks were alone in using local flowers like violets and peonies to add taste and fragrance to their food, and in a taste for big, eggy flans). Mostly, however, Europeans ate similar food everywhere, including continent-wide favourites we still enjoy today, such as rissoles, or meat balls. The same spicy sauces were found everywhere, too. Light, dry birds – turtledove, partridge, pigeon and quail – were served with nothing more than salt and lemon juice. Chicken and fried fish went with jance, a sauce of white wine, cider vinegar and ginger, cloves, and burned bread. A tangier green sauce (cider vinegar, ginger and hot herbs including parsley) was used with colder, moister boiled fish. Camelina, hotter still, was made of vinegar or read wine, toasted bread, and a spice mix including ginger, grain of paradise, clove, long pepper and cinnamon, and eaten with the crude meat of quadrupeds. Hot sauce – like camelina, but with more cloves – went well with venison, viscous fish such as lamprey or large eels and crude fish such as dolphins and porpoise. These could also be served with another very hot sauce – black pepper sauce, a blend of cider, vinegar, ginger, pepper and burnt bread.

Cloves and cardamom seem exotic flavours for the European cookpot of times gone by. It’s odd to realize that ginger, along with pepper, was one of the most popular cooking ingredients in the England of the Middle Ages, often sold ready-mixed with cinnamon and pepper as “blanchepowder” or “spicery”. But it’s important to remember that food at the time was not as we imagine European food today. Before fish and chips, nice cups of tea, pizza, potatoes, tomatoes and the heavy, glistening egg-and-oil-based sauces that dominated French and Italian cooking from the 17th century onwards, European food was more like contemporary Moroccan or Lebanese cooking – meat cooked with sweetening agents including honey and fruit, or sauced with the hottest of spices, and served with soft cheeses, nuts, and imported sugar, accompanied by the freshest of vegetables, oil or butter, wine, and dark bread from a variety of grains. According to Montanari, the typical tastes of the times were blends of sweet and salty, and bittersweet (blends of sugar and citrus, or honey and vinegar) – blended tastes still found in chutney with meat, or German peppercakes, or Moroccan honey-crusted pigeon.

Cloves and cardamom seem exotic flavours for the European cookpot of times gone by. It’s odd to realize that ginger, along with pepper, was one of the most popular cooking ingredients in the England of the Middle Ages, often sold ready-mixed with cinnamon and pepper as “blanchepowder” or “spicery”. But it’s important to remember that food at the time was not as we imagine European food today. Before fish and chips, nice cups of tea, pizza, potatoes, tomatoes and the heavy, glistening egg-and-oil-based sauces that dominated French and Italian cooking from the 17th century onwards, European food was more like contemporary Moroccan or Lebanese cooking – meat cooked with sweetening agents including honey and fruit, or sauced with the hottest of spices, and served with soft cheeses, nuts, and imported sugar, accompanied by the freshest of vegetables, oil or butter, wine, and dark bread from a variety of grains. According to Montanari, the typical tastes of the times were blends of sweet and salty, and bittersweet (blends of sugar and citrus, or honey and vinegar) – blended tastes still found in chutney with meat, or German peppercakes, or Moroccan honey-crusted pigeon.

Medieval cuisine was also characterized by an extremely sparing use of fats. “The cuisine of half a millennium ago was fundamentally lean,” Montanari writes. “To assemble sauces, the inevitable accompaniment to meat and fish, one used above all acidic ingredients such as wine, vinegar, citrus juice and the juice of sour grapes – ingredients to be bound with soft breadcrumbs, almond milk, and eggs. Fatty sauces, based on oil and butter, are more familiar to us. But they are modern.” These sauces remind Montanari of the sauces of Japanese or South-East Asian food today, because they’re thin, spicy and free of dairy products. I imagine them more with the Middle Eastern scents and tastes of the Ottolenghi or Moro cookbooks: the aroma of rosewater and orange blossom, the scattered petals of flowers, smoothness of almonds, the tang of cinnamon and thyme.

Medieval cuisine was also characterized by an extremely sparing use of fats. “The cuisine of half a millennium ago was fundamentally lean,” Montanari writes. “To assemble sauces, the inevitable accompaniment to meat and fish, one used above all acidic ingredients such as wine, vinegar, citrus juice and the juice of sour grapes – ingredients to be bound with soft breadcrumbs, almond milk, and eggs. Fatty sauces, based on oil and butter, are more familiar to us. But they are modern.” These sauces remind Montanari of the sauces of Japanese or South-East Asian food today, because they’re thin, spicy and free of dairy products. I imagine them more with the Middle Eastern scents and tastes of the Ottolenghi or Moro cookbooks: the aroma of rosewater and orange blossom, the scattered petals of flowers, smoothness of almonds, the tang of cinnamon and thyme.

Saffron, parsley, violets and cherries were used for their colour, and flowers for their scents, more than their taste. According to Paul Freedman’s Food: The History of Taste, visuals were all-important. Colouring beyond green and yellow came quicker to Anglo-Norman cuisine than to French, as did exotic colourants such as indigo. Coloured dishes of the day included a Saracen meal of ground chicken, rich almonds and sugar known as blanc desire, vert et janesere – white, green and yellow, with colours provided by parsley and saffron. Soup could sometimes be “departed” – two separate coloured pottages served swirled together in the same dish, a technique also used with jellies and custards. One 15th-century recipe for colouryd sew, a dish based on ground almonds and rice, spiced with white sugar, cloves, mace and cinnamon, came with the recommendation that it be served coloured: “let one part be white, the other yellow, and the other green with parsley.” Once the Crusaders brought home stories and goods from the Holy Land, the idea of serving golden food – embellished with gold leaf, and served on golden platters – also became prestigious.

Saffron, parsley, violets and cherries were used for their colour, and flowers for their scents, more than their taste. According to Paul Freedman’s Food: The History of Taste, visuals were all-important. Colouring beyond green and yellow came quicker to Anglo-Norman cuisine than to French, as did exotic colourants such as indigo. Coloured dishes of the day included a Saracen meal of ground chicken, rich almonds and sugar known as blanc desire, vert et janesere – white, green and yellow, with colours provided by parsley and saffron. Soup could sometimes be “departed” – two separate coloured pottages served swirled together in the same dish, a technique also used with jellies and custards. One 15th-century recipe for colouryd sew, a dish based on ground almonds and rice, spiced with white sugar, cloves, mace and cinnamon, came with the recommendation that it be served coloured: “let one part be white, the other yellow, and the other green with parsley.” Once the Crusaders brought home stories and goods from the Holy Land, the idea of serving golden food – embellished with gold leaf, and served on golden platters – also became prestigious.

Such transformations were only part of the general joy of preparing food.

Medievals brought all the science at their disposal to their ideas about nourishment. Another important theory had it that all cooking changed taste from cold to warm, transmuting each of nine basic flavours, from the coldest to the warmest, up one place in a scale that started with “acerbic” the colour of green fruits, which, ripened by the sun, would become sweet. Likewise, honey, which because temperate and sweet was further up the scale, would become bitter if caramelized by heat. The tropical sun gave pepper and other spices the hottest of all flavours – bitter and pungent.

Medievals brought all the science at their disposal to their ideas about nourishment. Another important theory had it that all cooking changed taste from cold to warm, transmuting each of nine basic flavours, from the coldest to the warmest, up one place in a scale that started with “acerbic” the colour of green fruits, which, ripened by the sun, would become sweet. Likewise, honey, which because temperate and sweet was further up the scale, would become bitter if caramelized by heat. The tropical sun gave pepper and other spices the hottest of all flavours – bitter and pungent.

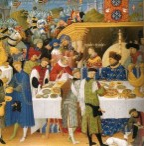

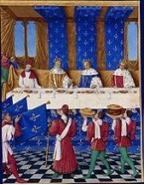

The medieval eating system made it easy for individuals at any table to choose the perfect combination of tastes for their own well-being. Food in the noble and ecclesiastical houses of medieval times was served collectively, to an entire household, in three or more great courses. But each course, rather in the manner of a Chinese or Japanese restaurant today, consisted of a choice of several different dishes and sauces. The great (including the Duke of Burgundy in the picture) ate with their physician behind them to tell them which dish was most appropriate for their particular personal state of health.

But the classification of foods – each with its degree of hotness, dryness, moisture or coldness – was so widespread and well-known that lesser mortals could make their own choices without difficulty.

This was important, because, for a medieval person, food choices were also a matter of social status.

At the simplest level, this was a matter of adapting your eating to changes in your lifestyle. Both morally and medically, it was thought dangerous to produce food which would produce excessive overheating for the body’s needs. The theologian and preacher Bernadino of Siena, for instance, preached in the Piazza del Campo that widows had to be careful to stop eating lust-provoking high-quality proteins now they no longer needed to be ready for sex. He told them they must avoid foods “that heat you up, since the danger is great when you have hot blood and eat food that will make you even hotter. … Do not try to do as you did when you had a husband and ate the flesh of fowl.”

At the simplest level, this was a matter of adapting your eating to changes in your lifestyle. Both morally and medically, it was thought dangerous to produce food which would produce excessive overheating for the body’s needs. The theologian and preacher Bernadino of Siena, for instance, preached in the Piazza del Campo that widows had to be careful to stop eating lust-provoking high-quality proteins now they no longer needed to be ready for sex. He told them they must avoid foods “that heat you up, since the danger is great when you have hot blood and eat food that will make you even hotter. … Do not try to do as you did when you had a husband and ate the flesh of fowl.”

But there was much more to the question of food and status than calming temporary unwelcome lusts. What food you ate defined your social status in more permanent ways.

There were widely accepted codes about which foods were appropriate for the mighty, and which more suitable for the meek. “Good” meat – the higher, flying fowl and game – were deemed most suitable for aristocrats, while merchants were thought to thrive on tougher, earth-bound quadrupeds. Especially large animals – giant capons or huge fish – were noble, too, and would be sent as presents to the highest-ranking, who were best fitted to eat them. Styles of cooking were rank-specific, too. Noblemen saw eating their meats roasted on a spit as a mark of prestige and prowess at hunting – a fighter’s manly style of eating, and, to this day, in its modern barbecue incarnation, a male preserve. Charlemagne, in his old age, was furious when doctors recommended he lay off the roast meats for a while to cure his gout, and ate less heroic cuts of boiled flesh instead.

Refined food fed the minds and souls of the highest-ranking, as well as their bodies, according to Florentin Thierriat, author of a 16th-century treatise on nobility. In Discours de la Preference de la Noblesse, Thierrat commented: “we eat more partridges and other delicate meats than they (non-nobles) do, and this gives us a more supple intelligence and sensibility than those who eat beef and pork.”

Refined food fed the minds and souls of the highest-ranking, as well as their bodies, according to Florentin Thierriat, author of a 16th-century treatise on nobility. In Discours de la Preference de la Noblesse, Thierrat commented: “we eat more partridges and other delicate meats than they (non-nobles) do, and this gives us a more supple intelligence and sensibility than those who eat beef and pork.”

If high-class food made noblemen suited to power, high rank actually brought with it a duty to eat power food. A 1404 letter from Ser Lapo Mazzei, a Florentine notary, bears this out. Mazzei was thanking a friend for a handsome gift of partridges – but only through gritted teeth. He had to accept the kindly meant gift, since otherwise it would go to waste, Mazzei explained, ungraciously. But partridge was far too grand a dish for him, now he was no longer a government official. It wasn’t like the old days, when as one of the Signori of Florence, it would have been his “duty to eat such fowl.” This was no more than the truth. Lords were required to eat great quantities of high-class meat, in an outward sign of their political power. But this sort of food was not fit for normal people, either medically or morally. Mazzei ends, grumpily, with the remark that in his current walk of life he’d really have preferred a “little barrel of salted anchovies.” Mazzei might have been relieved to know that, a century later, a less stern Bolognese doctor, Baldassare Pisanelli, would write that “partridges are only unhealthy for country folk.” But, on the whole, there was widespread consensus as to who could eat what – in particular, in a belief that must have made the rich feel more comfortable about the peasants they controlled, that the lower orders were better off eating lots of veg, and might be endangered by stuffing themselves with fine fare: “he who is used to turnips must not eat meat pies.”

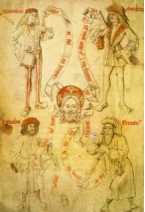

The idea was that the food world mirrored the human world, and the upper strata should therefore eat food from the upper realm of nature. And medieval minds knew exactly which foods went where in that natural pecking order of edibles – for that was laid out too, in great detail, in a ranking system known as the Great Chain of Being.

The idea was that the food world mirrored the human world, and the upper strata should therefore eat food from the upper realm of nature. And medieval minds knew exactly which foods went where in that natural pecking order of edibles – for that was laid out too, in great detail, in a ranking system known as the Great Chain of Being.

At the very bottom of this table came the element of earth, and the creatures of earth. Lowest in terms of status and nutritional value were bulbs grown underground, such as onions. Slightly above them came roots, like carrots. Above them were leaf vegetables, growing on the ground, including lettuce, and higher still fruits, which grew further from the ground and could be ripened by the sun’s heat. The pecking order for the element of water rose from molluscs to crustacea through fish to, at the top, dolphins and whales. When it came to air, a higher element still, the lowest birds were those that lived in the water, ducks and geese, then, a little higher, chickens and capons, which lived on the ground. More prestigious still were songbirds, a favourite of medieval and Renaissance cookery. At the very top were eagles and falcons, not as food but as the companions of noblemen, used for hunting food.

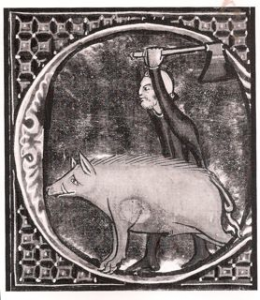

Quadrupeds didn’t fit easily into this system, as although they were earthbound, it was equally obvious they were not as low as vegetables. So they were slotted in somewhere at the side, in a class of their own, but with a pecking order of their own, too. Young meat, from lambs and kids and veal calves, came above old meat such as mutton or beef, and pork, the meat of the peasantry, came bottom of all.

Highest of all was the element of fire, but since the animals classified here were such fantastical beasts as phoenixes, dragons and unicorns, they didn’t make it to even the finest lord’s kitchen.

All these carefully worked out schemes and hierarchies gave members of every order of society ample choices of foods suitable for their status and purse, whether on feast and fast or fast days.

All these carefully worked out schemes and hierarchies gave members of every order of society ample choices of foods suitable for their status and purse, whether on feast and fast or fast days.

Noblemen ate mostly meat, wine and bread – the most expensive sorts of meat, seasoned with the finest spices or less exotic condiments, to keep them hot and battleworthy for a society which exalted physical strength and relied on it for defence. A heavy, excessive, stimulating diet was considered aristocratic. To eat a great deal was a sign of power, as well as a source of physical energy and sexual potency. The nobility’s bread was white and wheaten and their wine, preferably, sweet and white. (Water was frowned on for causing intestinal upsets). Eggs and cheese might accompany the aristocrat’s meats. Or, during fasts, a nobleman might cut back by eating either fish or eggs and cheese during fasts. Vegetables, which were served at table, were secondary. Fruit, although fretted over by doctors, became more popular.

Noblemen ate mostly meat, wine and bread – the most expensive sorts of meat, seasoned with the finest spices or less exotic condiments, to keep them hot and battleworthy for a society which exalted physical strength and relied on it for defence. A heavy, excessive, stimulating diet was considered aristocratic. To eat a great deal was a sign of power, as well as a source of physical energy and sexual potency. The nobility’s bread was white and wheaten and their wine, preferably, sweet and white. (Water was frowned on for causing intestinal upsets). Eggs and cheese might accompany the aristocrat’s meats. Or, during fasts, a nobleman might cut back by eating either fish or eggs and cheese during fasts. Vegetables, which were served at table, were secondary. Fruit, although fretted over by doctors, became more popular.

As for the peasantry, wheat and grain was their basic diet. The daily ration for one couple who paid the corvée, or tax of forced labour, in the French domain of Beaumont-le-Roger one large loaf and two smaller loaves, weighing in at about 2.25 kg, as well as a gallon of wine, half a pound of meat or eggs, and a bushel of peas. (This seems a lot, though there were no doubt children to feed; it’s worth remembering that physical labourers needed a lot of food to do their job, and the total energy value of what many physically active people of the time consumed appears to have been a good 5000-6000 calories a day, well above what more sedentary modern man considers necessary for his daily needs).

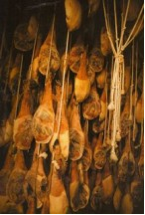

Peasants seldom received the white wheaten bread bought by the working class of the cities, but ate their own darker loaves of barley, rye, spelt or a mixture. Wine, too, was a substantial part of their food intake. Smaller quantities of proteins came from meat – mostly small farm animals, perhaps a pig left to graze in the woods until it was slaughtered in January, or a sheep too old to produce wool or milk; though also what eggs or cheese were left after the lord had taken his due.

Vegetables were vital for peasant cook-pots. Among the crops grown in the fields were broad beans, peas, and, in southern Europe, lentils and chickpeas. In the private vegetable garden at home, a peasant family might also grow cabbage, onions, garlic, leeks, turnips, spinach and squash, and gather herbs and greenery such as watercress, mushrooms, thyme, basil, marjoram, laurel, fennel and sage from the woods.

These ingredients allowed village women to make the peasant staple, soup, from small quantities of meat, lard or olive oil, sops of dry bread, with a great deal of vegetable and greens added.

On fast days, the peasantry might replace meat by cheese, dried fruit, eggs, possibly river fish or salt fish if they could afford it, and they’d swap their animal lard for olive oil.

We know far more about the feasting and fasting practices of churchmen, who, being literate and highly organized, wrote them down.

This is how the Benedictine monks of the Burgundian abbey at Cluny ate in the first part of the 13th century. The monks fasted on Wednesdays and Fridays, as well as during Advent, Lent, and on quarterly Ember Day and spring Rogation fasts established by the Church too.

From October 1 to Lent – the season of short, cold days – the community met in the refectory once on working days, and twice on feast days.

From October 1 to Lent – the season of short, cold days – the community met in the refectory once on working days, and twice on feast days.

Winter dinner was at noon (sext). It consisted of two hot vegetable dishes, one a fat-free soup and one a plate of cooked greens, and a third dish as supplement – either the General, which consisted of protein, in the shape of a plate of five eggs or some cooked cheese for every monk, and was served on non-fast days, or the Pittance of garden veg or fruit. The monks also got a pound of wheaten bread each, and about half a pint of undiluted wine.

In summer – from Easter till the end of September – the monks were given two meals a day, on ordinary days, though the number of meals dropped back to one on fast days. This was compensation for the hard work and heat of summer. Dinner was at noon (sext), and supper after vespers (5-6 pm). Supper was much more frugal than dinner – just the leftovers of bread and wine from dinner, along with fruit and wafers.

In the morning, after first prayers, duty monks, along with the sick and children, could have a bit of bread and some wine, a meal known as mixtum. A thirsty monk could also have a last drink before bed.

On fast days, the monks only had one meal, served at 3pm (nones). This was still after Vespers, but the evening service was brought forward so the monks wouldn’t be too hungry.

The meals on fast days were like ordinary meals – except during the most austere fasts, Lent and the quarterly ember days, when vegetables were cooked in oil, not animal lard (though there was more bread, in compensation). Penitential days for these monks, therefore, just meant a delay in serving the winter dinner, or, in summer, the elimination of supper from the day.

Feasts were something to look forward to.

At Cluny, the monks feasted on the day of Benedict of Nursia, their founder, as well as on the great feasts of the liturgical year, including Christmas and Easter. Instead of being given a daily food supplement of either the protein-laden General, or the fruity Pittance, on feast days the community would get both at once. The daily vegetable soup would likewise be replaced by something more exciting. And there would be not just bread – but also cake, made with eggs, and meat, and hippocras (mulled wine sweetened with honey, pepper and cinnamon).

Away in the privacy of the dining room for superior ecclesiastics and honoured guests, still finer fare might be on offer. But the ordinary monks would, on a feast day, feel they had too much on their own plates to care.

After my own forty days of a much more pedestrian diet version of Lent – one meal of plain meat or fish a day, cooked without cream or fatty sauces, though often with unfattening ginger and oriental spices – I reverted to the healthier weight I used to be before having children and adopting a stressed, thoughtless modern lifestyle of eating whatever came my way, on the hoof, without ever really pausing to consider or enjoy it. I embarked on the diet thinking that making all my own food myself, from scratch, with real raw ingredients, avoiding the hidden sugar and fats modern manufacturers seem to slip into every can and packet, might be a time-consuming pain. But, to my surprise, I found myself enjoying having to give time to organise and plan what I’d eat, and when, and how to eke out the tiny bits of olive oil and dairy my regime allowed me. This wasn’t unlike a monkish diet of half a millennium ago – dominated by vegetables, small amounts of milk and cheese, and slightly more animal protein, mostly chicken and fish, all highly and carefully spiced, with, also, grains added to soups and broths, and, increasingly, as the diet came to an end, with wholemeal bread and nuts and fats, both animal and vegetable, added back in too. The biggest difference was the alcohol – medieval people drank alcohol drinks to quench their thirst, instead of water, which was thought an unwholesome substance in those days, feared for causing intestinal upsets (all those dead sheep upstream) – whereas I can’t remember the taste of the last wine I drank, back on Shrove Tuesday. My diet did more than reduce my proportions. It also took away all the mysterious joint aches and fleeting back pains that used to bother me – so, health benefits too. My pseudo-“Lenten” fast did the job.

After my own forty days of a much more pedestrian diet version of Lent – one meal of plain meat or fish a day, cooked without cream or fatty sauces, though often with unfattening ginger and oriental spices – I reverted to the healthier weight I used to be before having children and adopting a stressed, thoughtless modern lifestyle of eating whatever came my way, on the hoof, without ever really pausing to consider or enjoy it. I embarked on the diet thinking that making all my own food myself, from scratch, with real raw ingredients, avoiding the hidden sugar and fats modern manufacturers seem to slip into every can and packet, might be a time-consuming pain. But, to my surprise, I found myself enjoying having to give time to organise and plan what I’d eat, and when, and how to eke out the tiny bits of olive oil and dairy my regime allowed me. This wasn’t unlike a monkish diet of half a millennium ago – dominated by vegetables, small amounts of milk and cheese, and slightly more animal protein, mostly chicken and fish, all highly and carefully spiced, with, also, grains added to soups and broths, and, increasingly, as the diet came to an end, with wholemeal bread and nuts and fats, both animal and vegetable, added back in too. The biggest difference was the alcohol – medieval people drank alcohol drinks to quench their thirst, instead of water, which was thought an unwholesome substance in those days, feared for causing intestinal upsets (all those dead sheep upstream) – whereas I can’t remember the taste of the last wine I drank, back on Shrove Tuesday. My diet did more than reduce my proportions. It also took away all the mysterious joint aches and fleeting back pains that used to bother me – so, health benefits too. My pseudo-“Lenten” fast did the job.

Or did it? Reading about the Middle Ages made me wonder. My diet was only ever a body thing – a physical fix, using diet in its modern sense as punishment and self-denial. It was a struggle between greed and willpower, a tussle between mind and body.

How much more pleasurable, and healthful, it might have been to stop thinking of it as a struggle at all? I might instead have embraced the far bigger idea that medievals lived by – of bringing mind, body and spirit into complete harmony by observing the medieval rhythms of feast and fast for a full year.

To anyone from our guilt-ridden, angsty age, it seems almost inconceivable that we might achieve the glowing, meditative peace of mind that this promises – while, at the time, being allowed, on two days out of every three, to consume tender turtle-dove in honey, or gingery sauce on a fillet of lamprey, or a custard scattered with rosewater sugar and gleaming with gold leaf. But our medieval ancestors did. Surely it was their faith that eating beautifully and appropriately – no less than praying, or thinking, or fasting – was part of the cosmic plan, that made this ordered way of life so popular across Europe for a thousand years. We could do worse than to try it again.

To anyone from our guilt-ridden, angsty age, it seems almost inconceivable that we might achieve the glowing, meditative peace of mind that this promises – while, at the time, being allowed, on two days out of every three, to consume tender turtle-dove in honey, or gingery sauce on a fillet of lamprey, or a custard scattered with rosewater sugar and gleaming with gold leaf. But our medieval ancestors did. Surely it was their faith that eating beautifully and appropriately – no less than praying, or thinking, or fasting – was part of the cosmic plan, that made this ordered way of life so popular across Europe for a thousand years. We could do worse than to try it again.

What a wonderful article! The medieval diet and medical philosophy outlined here reminds me greatly of Chinese medicine and the use of food, warming, cooling etc. to counter-balance certain conditions. Five elements used there (which also embraces their version of ‘humours.’ The wide spectrum of foods used is also similar. Eating local food and in season would also have been inevitable in a medieval society, of course, which is another reason for considering this kind of age-old wisdom in our own times. If only they would have had our clean drinking water, too, they would have been living to 100 probably!

Great post! Thanks Vanora! I find food history fascinating. I have read Paul Freedman’s History of Taste as cited in the article. Great book with lots of lovely pictures too. I also have his book Out of the East: Spices in the Medieval Imagination, that I haven’t read yet.

Thanks again Vanora, for the article, and for bringing us such wonderful books too!

I so enjoyed this article! Every year after reading Romeo and Juliet, I have my students research medieval recipes and produce them — with some interesting results, I might add! This article will be of great use in the unit! Thanks!!

That sounds fabulous Penny! I am glad that article will help in your unit. Vanora is a very clever lady!

Thank you, so interesting, and I’ve bought the Freedman book too now!

I’ve read many references that suggest people did not drink beer or ale because the water was bad. They, unlike us, had plentiful unpolluted streams. Here is one article that deals with the point but there are many others

https://knowledgenuts.com/bad-water-never-made-people-drink-beer-instead/