By Sandra Byrd

God Speed! by Edmund Blair Leighton, 1900: a late Victorian view of a lady giving a favor to a knight about to do battle

The art of courtly love and chivalric romance so popular during the early medieval period saw a revival during the Tudor era. Because the majority of noble marriages were arranged, with the focus being on financial or political gain, courtly love was a gentle, parrying game of flirtation wherein people might express true, heart-felt affections. According to historian Eric Ives, “The courtier, the ‘perfect knight’, was supposed to sublimate his relations with the ladies of the court by choosing a ‘mistress’ and serving her faithfully and exclusively. He formed part of her circle, wooed her with poems, songs and gifts, and he might wear her favor and joust in her honor … in return, the suitor must look for one thing only, ‘kindness’ – understanding and platonic friendship.” Many of the plays and entertainments in Henry the Eighth’s court reflected these values and Henry himself, early in his reign, was very chivalrous and courtly indeed.

Andreas Capellanus, in his definitive twelfth century book, The Art of Courtly Love, set out to inform “lovers” which gifts could be offered, (among them a girdle, a purse, a ring, or gloves) and to clarify the signs and signals that indicated such a love game was underway – or on the wane. This way the participants, and those around them at court, would know that the game was afoot. Physical attraction was one of many factors in courtly love, but sexual expression was not necessarily an element of the relationship. Cappellanus further posits that a beautiful figure, excellence of character, and extreme readiness of speech are required for a man or woman to fall in love, with character being the most noble element of all.

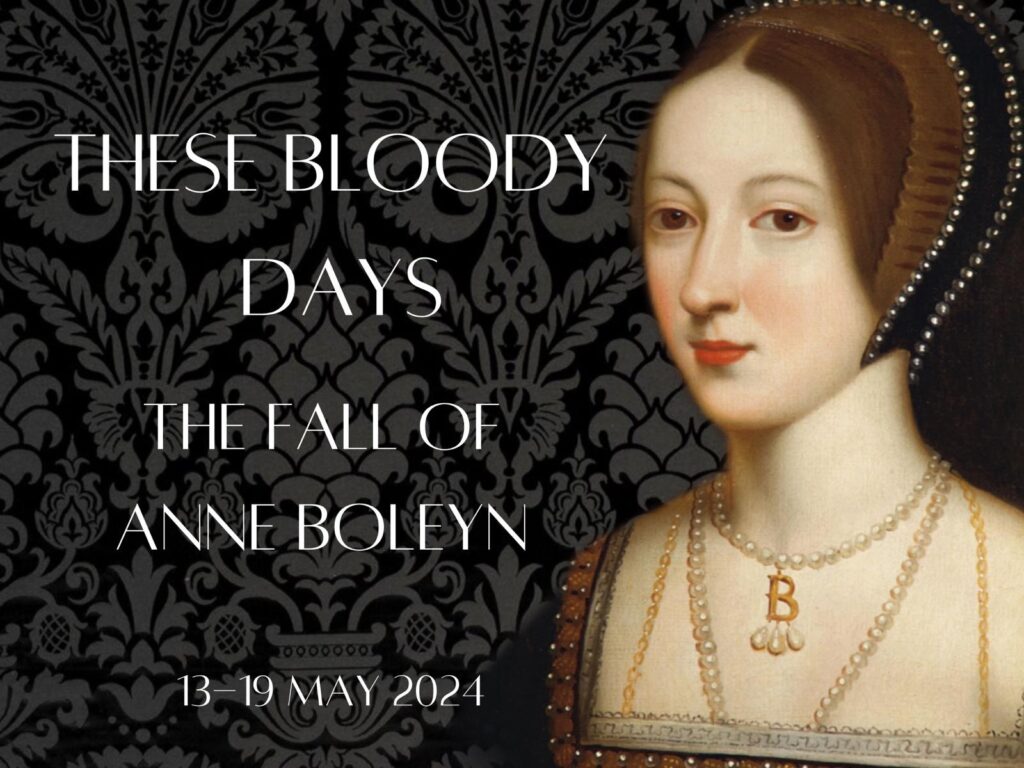

The longest game of courtly love, played out before all of Europe, was undoubtedly between Anne Boleyn and Henry VIII. The relationship started out as courtly flirtation but as sometimes happened, it then progressed to a more serious, deeper connection with a significant goal in outcome and purpose. Although their courtly relationship did not follow each of the thirty-one rules Capellanus lists from the “King of Love,” it did dovetail with some of them – a few of which have been examined below.

Rule II. He who is not jealous cannot love. This rule immediately brings to mind the incident between Henry and Thomas Wyatt during a game of bowls. Thomas Wyatt used one of Anne’s ribbons and bauble to mark distance, and he meant to use it to provoke or test Henry’s jealousy. Henry, predictably, flew into a possessive bluster. Anne recovered nicely from Wyatt’s foolishness, but there was no further doubting that she was Caesar’s and not to be touched.

Rule IV. It is well known that love is always increasing or decreasing. One of the most extraordinary things about Henry’s affection for Anne is that she was able to not only capture it but build upon it over a remarkable period of time – seven years from 1525 when it was clear he had fallen for her, to 1533 when their public marriage took place – allegedly, without physical consummation. He did not become bored or disinterested in her companionship. This was no mean feat when one considers Henry’s short attention span. He wrote tender love letters to Anne, some of which still exist, a powerful demonstration of his growing love as Henry loathed writing.

Rule XI. It is not proper to love any woman whom one would be ashamed to seek to marry. Much has been made of the fact that Anne “held out” sexually from Henry for personal reasons, and that Henry wanted his heirs by her to be legitimate, two among other valid reasons why they did not simply have an affair. But there is strong evidence to suggest that Henry found Anne worthy of marriage – he crowned her –and took great pride in displaying her before all the court. In Anne it is clear that for some time Henry believed he’d found a spirited soul mate who was as vibrant as he was and he desired for her to be his wife.

Rule XIV. The easy attainment of love makes it of little value; difficulty of attainment makes it prized. We’re often reminded that Henry left his wife and broke away from the Roman Catholic Church during his pursuit to marry Anne, courting war and ill will in the process. But Anne, too, made sacrifices. Her child-bearing years were quickly slipping by; there was a rush to judgment as she was reviled by much of the populace as a usurper; she had no official role nor position; and, finally, there was no guarantee that she would even have her marriage. Both of them risked much. Only one of them, in the end, lost everything.

Rule XXVIII. A slight presumption causes a lover to suspect his beloved. In the end, it took very little to convince Henry that Anne had betrayed him, a ridiculous acceptance of circumstances that demanded Anne be in places she clearly was not and act in ways that would never have gone unnoticed and that were in stark contrast to her character. . One must ask, why? Cappellanus answers that question for us, too.

“…when love has definitely begun to decline, it quickly comes to an end unless something comes to save it.”

At the point when the King’s affections began their precipitous drop, long after their game of courtly love was over and well into their marriage, the only thing that could have saved Anne was the son she miscarried. Chivalric values included integrity, protecting the vulnerable, and acting with self-sacrificing honor. Sadly, Henry did not turn out to be the “perfect knight” Ives speaks of. In Capellanus’s concluding section, The Rejection of Love, he references , “…lovers who have been driven by love to think of killing their wives and they have even put them to a very cruel death – a thing which all will agree is an infamous crime.” Unfortunately, this evil came to pass. In Anne’s final months, Henry was likely not driven to this crime by love of another woman, although he clearly had one in mind, but perhaps primarily out of love for himself, a nonvalorous motivation indeed.

Learn more about Sandra’s books here: http://www.sandrabyrd.com or purchase her new book about Anne Boleyn, told from the point of view of Meg Wyatt, here: To Die For

Wonderful post, thanks for sharing! It seems like courtly love walked a very fine, tenuous line and it is no wonder it didn’t always stay as innocent as it started :).

Hi Nathalie, I loved the post! Very good indeed, very informative. I found this article very interesting to have read and loved! It’s those little details that make me more curious about the story of Anne Boleyn and Henry VIII. I always want to go back in time just to see the two of them closely and follow their story.